|

|||

|

And now, after the edict of total destruction of the German enemy, one can no longer hear the sounds of this venerable Jewish town. It is hard to come to terms with the depressing thought that, indeed, the Jewish community of Sudilkov has been wiped off the face of the earth. (Shprintza Rokhel, 1948) In the history of the human race, no single people has ever tested the depths of barbarity, cruelty, depravity and madness as have the Germans and their cousins the Austrians. The magnitude of their horrific crimes cannot be calculated, and the damage they have wrecked upon European civilization cannot be quantified. Yet, of all their vicious and cowardly acts, their attempt to murder all the world’s Jews stands out as a monument to evil. In the period 1941 to 1945 the Germans and Austrians, guided by a totalitarian regime, systematically massacred over eleven million unarmed civilians, six million of whom were Jews. Women, children, the young, elderly, and handicapped, artists, intellectuals, rabbis and priests were shot and buried in excavated ditches, or driven into concentration camps and tortured, shot, gassed, and cremated. Others were experimented upon and dissected. Incredibly, all of this occurred during the lifetime of my father! I, for one, will never pardon them for what they have done, nor will my children and grandchildren. Let this chapter serve as a memorial to our European ancestors, most—if not all—of whom were murdered in 1941-1942.

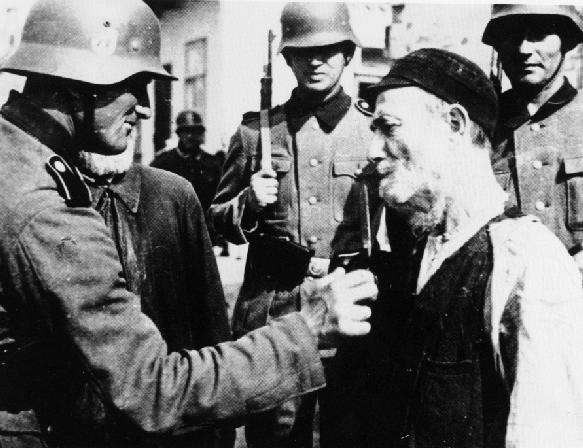

A Jew is brutalized by Nazi soldiers There is a short summary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union posted on the website of the Simon Weisenthal Center: “In 1940 German forces continued their conquest of much of Europe, easily defeating Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. On June 22, 1941, the German army invaded the Soviet Union and by September, was approaching Moscow. Operation Barbarossa, as Hitler called it, involved 3.5 million German and Austrian soldiers organized into 190 divisions. By June 30 the Nazis had already captured Lvov. On July 15 they overran Berdichev and at the end of the month they reached Kirovohrad. In the meantime, Italy, Romania, and Hungary had joined the Axis powers led by Germany and opposed by the Allied Powers: the British Commonwealth, Free France, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

Jews marched away by the SS “In the months following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Jews, political leaders, communists, and many Gypsies were killed in mass executions. The overwhelming majority of those killed were Jews. These murders were carried out at improvised sites throughout the Soviet Union by members of mobile killing squads called ‘Einsatzgruppen’ who followed in the wake of the invading Germany army.

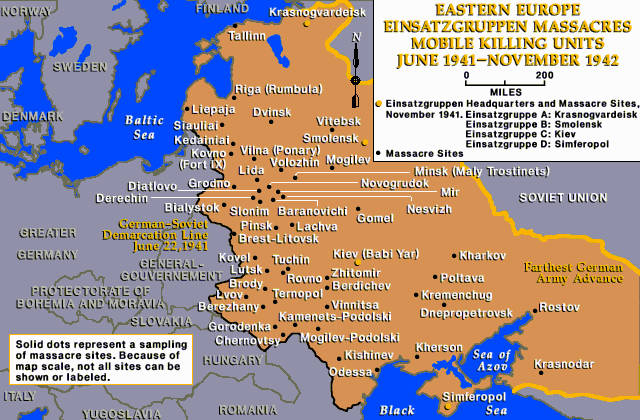

German advance into Russia and Einsatzgruppen activities The most famous of these sites was Babi Yar, near Kiev, where an estimated 33,000 persons, mostly Jews, were murdered. German terror extended to institutionalized, handicapped and psychiatric patients in the Soviet Union; it also resulted in the mass murder of more than three million Soviet prisoners of war.”

Nazi soldier executes a man before a mass grave The Einsatzgruppen, often assisted by the local police, were responsible for shooting 1.25 million Jews and other Soviet nationals, including more than half the Jews in the Ukraine. A large number of Ukrainians actively participated in the murder and despoliation of their Jewish neighbors. In the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (Macmillan Publishing Co., New York, 1990) there is a highly informative chapter on the Einsatzgruppen, which I cite at length: Full name, Einsatzgruppen des Sicherheitsdienstes [SD] und der Sicherheitspolizei [Sipo]; Operational Squads of the Security Service and the Security Police; task force of mobile killing units operating in German-occupied territories during World War II: Einsatzgruppen made their first appearance during the Anschluss, the incorporation of Austria into the Reich in March 1938. These were intelligence units of the police accompanying the invading army; they reappeared in the invasion of Czechoslovakia, in March 1939, and of Poland, on September 1 of that year. In the invasions of Austria and Czechoslovakia, the task of the Einsatzgruppen was to act as mobile offices of the SD and the Sipo until such time as these formations established their permanent offices; they were immediately behind the advancing military units, and, as in the Reich, they assumed responsibility for the security of the political regime. In the Sudetenland, the Einsatzgruppen, in close cooperation with the advancing military forces, lost no time in uncovering and imprisoning the “Marxist traitors” and other “enemies of the state” in the liberated areas.

A woman and her child are executed

Six Einsatzgruppen were organized on the eve of the Polish invasion; five were to accompany the invading German armies, and the sixth was to operate in the Poznan area, which was to be incorporated into the Reich as the Warthegau. Each Einsatzgruppe was subdivided into several Einsatzkommandos, one each to an army corps. There were fifteen Einsatzkommandos, each with a complement of one hundred twenty to one hundred fifty men. Einsatzgruppe personnel were recruited from among the SD, Sipo, and SS, on a regional basis. The Einsatzgruppen did their work in accordance with policy lines for foreign operations issued by the Sipo and SD. These policy lines had been laid down as early as August 1939 by Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office; RSHA), and by Generalquartiermeister Eduard Wagner, the WEHRMACHT representative in that office. The basic instruction was to combat, in enemy countries, elements in the rear of the front-line units who were hostile to the Reich and to Germans. A more detailed description of the Einsatzgruppen’s mission is contained in an order of the day issued by the Eighth Corps: “To conduct counterespionage, to imprison political suspects, to confiscate arms, and to collect evidence that is of importance to police intelligence work.” In practice, “combating hostile elements” was given a broad interpretation and became terror operations on a grand scale against Jews and the Polish intelligentsia, in which some fifteen thousand Jews and Poles were murdered. On September 21, 1939, Heydrich sent a high-priority note to the Einsatzgruppe commanders giving instructions for the treatment of Jews in the conquered territories. The Jews were to be rounded up and concentrated in large communities situated on railway lines; Judenrate (Jewish councils) were to be established; and operations against the Jews were to be coordinated with the civil administration and the military command. On November 20 of that year, on orders from Berlin, the Einsatzgruppen’s operations were terminated and their personnel were absorbed by the permanent SD and Sipo offices in occupied Poland. When the plans were drawn up for the attack on the Soviet Union, ample use was made of the experience these men had gained, and four Einsatzgruppen were reestablished as A, B, C, and D. In briefing sessions with the German army commanders on the planned Operation “Barbarossa”, Adolf Hitler emphasized that the impending war with the Soviet Union would be a relentless struggle between two diametrically opposed ideologies. Its success would be determined not only by military victories, but also by the ability to root out and destroy the propagators of the rival ideology and its adherents. Hitler entrusted this job, of liquidating the personnel of the Soviet political and ideological apparatus, to Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and of all German police formations (Reichsfuhrer-SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei). Decree 21, Hitler’s order for Operation “Barbarossa”, in the section “Instructions for Special Areas,” states: “In areas where military operations are being conducted, the Reichsfuhrer-SS, in the name of the Fuhrer, will assume the special duties required for setting up the political administration.... In the discharge of these duties the Reichsfuhrer will operate independently and on his own authority.... The Reichsfuhrer will ensure that the pursuit of his objectives will not interfere with military operations. Details will be worked out directly between the High Command and the Reichsfuhrer-SS.” After consultations between Heydrich (acting as Himmler’s representative) and Eduard Wagner, Gen. Walther von Brauchitsch, the commander in chief of the army, issued an order stating that for the fulfilling of special security police assignments that went beyond the scope of military operations, special units of the SD would be employed in the army’s operational area. These units were to proceed according to the following guidelines: “The special units will operate in the rear of the fighting forces and their task will be to seize archives, to obtain lists of organizations and anti-German societies, and to look for individuals such as exiled former political leaders, saboteurs, and the like; they will uncover any existing anti-German movements and liquidate them; and they will coordinate their activities in these areas with the military field-security apparatus.” The order adds that while the Sipo and the SD (including the Einsatzgruppen) would be operating on their own responsibility, as far as logistics were concerned they would be attached to the armed forces and would depend upon the latter for housing, rations, transport, communications, and other matters. To ensure the proper coordination, representatives of the SD and Sipo would be attached to corps and army headquarters. In its concluding section, the order provides that the special units were empowered to take administrative action against the civilian population, on their own responsibility but in cooperation with the military police, and with the approval of the local Wehrmacht commander. (For example, the extermination of the Kiev Jews at Babi Yar was decided on at a meeting held in the office of the military governor of the city, General Eberhardt, with the general attending and concurring in the decision.) By this order, which faithfully reflects the agreement arrived at by Heydrich and Wagner, the Wehrmacht relieved itself of the task of carrying out mass murder, and restricted its involvement to logistics. However, under the conditions that developed in the occupied areas of the Soviet Union, the cooperation between the Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen from time to time went beyond the provisions of the agreement, as when military units were deployed to stand guard over individuals or groups of persons who had been condemned to die, or over the area designated for their execution. Early in May 1941, the men who had been chosen as candidates for the Einsatzgruppen were assembled in the training school of the German border guard in Pretzsch (a town on the Elbe River, northeast of Leipzig). The school did not have enough space to hold all the candidates, and some had to be quartered in the neighboring towns of Duben and Bad Schmiedeberg. Most of the candidates had come from the RSHA, whose manpower division had ordered the SD and the Sipo to select suitable men for this purpose. Another group of candidates came from the Sipo senior officers’ training school in Berlin; yet another group, of 100 men, had been attending an officer candidates’ school of the Kriminalpolizei (Criminal Police), and were dispatched from there to join the Einsatzgruppe candidates at Pretzsch. The commanding officers of the Einsatzgruppen, the Einsatzkommandos, and the Sonderkommandos were chosen by Himmler and Heydrich from a list prepared by Section I of the RSHA; most had been serving as senior officers of the SD. The technical staff of the Einsatzgruppen—radio operators, clerks, interpreters, drivers, and others—were recruited from among the staff of the RSHA and the SS. Three of the Einsatzgruppen—B, C, and D—had attached to them companies of Reserve Police Battalion No. 9, later replaced by men from Battalion No. 3, as well as companies of the Waffen-SS, for special duties. Each of the reestablished Einsatzgruppen had sub-units, usually called Einsatzkommandos or Sonderkommandos. In theory, the Einsatzkommandos were to be attached to the armed forces behind the lines and the Sonderkommandos to those forces at the front. In practice, however, the Einsatzgruppen and their sub-units were deployed according to geographic sectors and not according to rear or front-line areas. The distinction between the Einsatzkommandos and the Sonderkommandos evaporated. Both the Einsatzkommandos and the Sonderkommandos also had temporary sub-units, usually referred to as Teilkommandos (lit., “part commandos”). When they were charged specifically with entering a town or city, they were sometimes called Vorkommandos (forward commandos). The composition of the Einsatzgruppen was as follows: Einsatzgruppe A consisted of Sonderkommandos SK1a, SK1b; and Einsatzkommandos EK2, EK3.2. Einsatzgruppe B consisted of Sonderkommandos SK7a, SK7b; Einsatzkommandos EK8, EK9; and Vorkommando (V - KO) Moskau (SK7c).3. Einsatzgruppe C consisted of Sonderkommandos SK4a, SK4b; and Einsatzkommandos EK5, EK6.4. Einsatzgruppe D consisted of Sonderkommandos SK10a, SK10b; and Einsatzkommandos EK11a, EK11b, EK12. The first commander of Einsatzgruppe A, SS-Standartenfuhrer Dr. Franz Walter STAHLECKER, had about one thousand men at his disposal. Einsatzgruppe A was attached to Army Group North; its area of operations covered the Baltic states (LITHUANIA, LATVIA, and ESTONIA) and the territory between their eastern borders and the Leningrad district. The first commander of Einsatzgruppe B, SS-Brigadefuhrer (later Gruppenfuhrer) and Generalleutnant der Polizei Arthur Nebe, had 655 men under his command. The Einsatzgruppe was attached to Army Group Center, and its operational area extended over Belorussia and the Smolensk district, up to the outskirts of Moscow. The sub-unit of Einsatzgruppe B that was deployed toward Moscow was called Vorkommando Moskau. When the German forces began their withdrawal from Moscow, the Vorkommando was disbanded. The first commander of Einsatzgruppe C, SS-Standartenfuhrer Dr. Emil Otto rasch, had seven hundred men under his command; the Einsatzgruppe was attached to Army Group South and covered the southern and central Ukraine. Einsatzgruppe D, commanded by SS-Standartenfuhrer Professor Otto Ohlendorf, had a complement of six hundred men. It was attached to the Eleventh Army and operated in the southern Ukraine, the Crimea, and Ciscaucasia (the Krasnodar and Stavropol districts). On the face of it, the units, relatively small in size, had a very large area to cover. However, when they were engaged in mass-murder operations, the Einsatzgruppen were assisted by large forces of German police battalions and local auxiliary police battalions—Ukrainian, Belorussian, Latvian, or Lithuanian. At times they also had rear echelon troops at their disposal, such as garrison battalions, military gendarmeries, or even soldiers of the Organisation Todt. In early June 1941, Bruno Streckenbach, head of Branch I of the RSHA, came to Pretzsch in order to explain, on behalf of Himmler and Heydrich, Hitler’s orders concerning the liquidation of the Jews. After the war, Ohlendorf gave evidence on the meeting with Streckenbach before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals, at the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings, as did Dr. Walter Blume, who had been the commanding officer of Sonderkommando 7a. In his statement, Blume declared that in June 1941 Heydrich and Streckenbach had briefed them on their assignment of exterminating Jews, and had explained the ideological background. A large number of Einsatzgruppe, Einsatzkommando, and Sonderkommando commanders had taken part in the briefing sessions. Another such session, attended by the commanders of all units and sub-units, took place on June 17, 1941, in Heydrich’s office in Berlin. At this time, Heydrich set out in detail the policy that was to guide the Einsatzgruppen in carrying out their assignments, among them the implementation of the Fuhrer’s order to liquidate the Jews. A third such meeting, also very close to the date of the invasion of the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941), was held in the office of the chief of the Ordnungspolizei, Kurt Daluege. It was attended by the senior SS and police officers who had been designated to act as Einsatzgruppe commanders in the various parts of the Soviet Union, when these were occupied by the German army. On July 2, 1941, these officers also received written instructions from Heydrich, which contained the following passage: “The following is the gist of the highly important orders that I have issued to Einsatzkommandos of the Sipo and the SD, with which these two services are called upon to comply.... 4) Executions. The following categories are to be executed: Comintern officials (as well as all professional Communist politicians); party officials of all levels; and members of the central, provincial, and district committees; people’s commissars; Jews in the party and state apparatus; and other extremist elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins, agitators, etc.).” The order affecting the ‘Jews in the party and state apparatus’ encompassed, in practice, all the Jews in the Soviet Union. Einsatzgruppe Report No. 111 of October 12, 1941, did in fact make it perfectly clear that the purpose was to kill all Jews. With these orders in mind, the Einsatzgruppen began their march into the Soviet Union, in the footsteps of the German army. Einsatzgruppe A started out from East Prussia, and its units—the Sonderkommandos and Einsatzkommandos—rapidly spread out across Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. On June 25, Einsatzgruppe A headquarters entered Kovno at the same time as the advance formations of the army, and at the beginning of July it moved to Riga. The local auxiliary police (made up of Lithuanians or Latvians), together with the Einsatzgruppe’s various units, embarked upon the massacre of Jews, mainly in Vilna (Ponary), Kovno (the Ninth Fort), and Riga (Rumbula), as well as in many other cities and towns. Next, Einsatzgruppe A and several of its sub-units advanced toward Leningrad, so as to be able to enter the city together with the Totenkopf Division of the Waffen-SS. When the Leningrad front stabilized, Einsatzgruppe A was for the most part disbanded, and some of its personnel were used to establish and staff the regional SD and Sipo offices. At the end of September 1941 Dr. Stahlecker, the Einsatzgruppe A commander, was also appointed SS and Sipo commander (Befehlshaber der Sicherheitspolizei und des Sicherheitsdienstes) of Reichskommissariat Ostland. Small and mobile sub-units of Sonderkommandos 1a and 1b continued to “clean up” the area between the Baltic states and the eastern front. Einsatzgruppe B had Warsaw as its starting point; some of its units passed through Vilna and Grodno on the way to Minsk, where they arrived on July 5, 1941. Other units belonging to Einsatzgruppe B passed through Brest-Litovsk, Slonim, Baranovichi, and Minsk, and from there proceeded to southern Belorussia: Mogilev, Bobruisk, and Gomel, advancing as far as Briansk, Kursk, Orel, and Tula. Along their route, in all the places through which they passed, they murdered masses of people—Jews, Gypsies, Communist activists, and prisoners of war. At the beginning of August 1941, Einsatzgruppe B headquarters moved to Smolensk, and some of its units were deployed in northern Belorussia, in places such as Borisov, Vitebsk, and Orsha. Two months later the headquarters moved again, to Mozhaisk, while its special advance unit, Vorkommando Moskau, established itself in Maloyaroslavets; both expected to enter Moscow with the Fourth Panzer group of the German army. Einsatzgruppe C made its way from Upper Silesia to the western Ukraine, by way of Krakow. Two of its units, Einsatzkommandos 5 and 6, went to Lvov, where they organized a pogrom against the Jews with the participation of Ukrainian nationalists. Sonderkommando 4b organized the mass murders at Ternopol and Zolochev, and then continued on its way to the east. Einsatzgruppe C headquarters and Sonderkommando 4a went to Zhitomir, by way of Volhynia, with 4a carrying out massacres en route, in Dubno and Kremenets. On September 29 and 30, Sonderkommando 4a, commanded by Paul Blobel, perpetrated the mass slaughter of Kiev Jews at Babi Yar. This unit was also responsible for the murder of Kharkov’s Jews, in early January 1942. Einsatzkommando 6 marched to the east and undertook the liquidation of the Jews of Krivoi Rog, Dnepropetrovsk, and Zaporozhye, proceeded to Stalino (Donetsk), and reached Rostov-on- Don. Einsatzkommando 5 was then broken up into SD and Sipo teams to staff local offices of the two organizations in such cities as Kiev and Rovno. In Rovno, the capital of Reichskommissariat Ukraine, these teams launched a large-scale Aktion at the beginning of November 1941, in which most of the Jewish inhabitants were murdered. Einsatzgruppe D, as mentioned, was attached to the Eleventh Army. During its advance it carried out massacres in the southern Ukraine (Nikolayev and Kherson), in the Crimea (Simferopol, Sevastopol, Feodosiya, and other places), and in the Krasnodar and Stavropol districts (Maykop, Novorossisk, Armavir, and Piatigorsk). By the spring of 1943, when the Germans began their retreat from Soviet territory, the Einsatzgruppen had murdered 1.25 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of other Soviet nationals, including prisoners of war. Jewish prisoners of war were separated from the rest and put to death at an early stage, in the advance transit camps.

Einsatzgruppen in action The method that the Einsatzgruppen employed was to shoot their victims in ravines, abandoned quarries, mines, antitank ditches, or huge trenches that had been dug for this purpose. The killing by shooting, especially of women and children, had a devastating effect on the murderers’ mental state, which even heavy drinking of hard liquor (of which they were given a generous supply) could not suppress. This was among the primary factors that led the RSHA in Berlin, in August 1941, to look for an alternative method of execution. It was found in the form of gas vans - heavy trucks with hermetically sealed vans into which the trucks’ exhaust fumes were piped. Within a short time these trucks were supplied to all the Einsatzgruppen. The Einsatzgruppen performed their murderous work in broad daylight and in the presence of the local population; only when the Germans began their retreat was an effort made to erase the traces of their crimes. This was the job of Sonderkommando 1005: to open the mass graves, disinter the corpses, cremate them, and spread the ashes over the fields and streams. In practice, the Einsatzgruppen left behind an immense record of their deeds, in the form of summary reports drawn up in Berlin on the basis of detailed reports submitted by the various units in the field. Among the most comprehensive of these summary reports was the Ereignismeldung der USSR (Report of Events in the USSR), which was first issued on June 23, 1941, and was continued until Report No. 195, dated April 24, 1942. Next, and in continuation, came the Meldungen aus den besetzten Ostgebieten (Reports from the Occupied Eastern Territories), which began on May 1, 1942, and were kept up until May 21, 1943. In addition, there were the reports on the operations and the situation of the SD and Sipo in the USSR, covering the period from June 22, 1941, to March 31, 1942. After the war, the Einsatzgruppe leaders were tried at the subsequent Nuremberg proceedings, in the ninth trial conducted by the Nuremberg Military Tribunals. The trial, The United States of America v. Otto Ohlendorf et al., was presided over by Judge Michael A. Musmanno. It began on July 3, 1947, and ended on April 10, 1948; there were twenty-four defendants. Fourteen of them were sentenced to death, seven to periods of imprisonment ranging from ten years to life, and one to the time already served; two were not tried or sentenced. Four of the defendants were actually executed, and sixteen had their sentences commuted or reduced to periods extending from the time already served to life imprisonment. One defendant was released, one died of natural causes, one committed suicide, and the execution of one was stayed because of the defendant’s insanity. Following the

establishment of the Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen (Central

Office of the Judicial Administrations of the Lander) at Ludwigsburg, West

Germany, over one hundred more indictments were handed down against

Einsatzkommando commanders, officers, noncommissioned officers, and privates.

In the ensuing trials no death sentences were passed, since the Federal

Republic of Germany had abolished capital punishment. Evidently, Einsatzgruppe C was the mobile killing division responsible for liquidating the Jews of Volhynia, including the inhabitants of the town of Sudilkov, which was occupied by the Nazis on July 4, 1941.

A Sonderkommando or Einsatzkommando, charged with exterminating all the Jews in the region, arrived in Sudilkov on July 21, 1941, only a day after Joseph Goebbels’ famous anti-Semitic article “Mimicry” was published. In it he proclaimed, “The Jews talk as if they were really strong, but soon they will have to move their tents and run like rabbits from the approaching German soldiers. Qui mange du juif, en meurt!” The unit swept eastwards so quickly that the townsfolk probably had little or no warning of the catastrophe which awaited them. One day they heard the low rumbling sound of approaching vehicles. The next thing they knew, a detachment of tanks and personnel carriers was roaring into town down the main street. Hundreds of soldiers armed with guns and dogs quickly descended upon them, shouting out orders in German as they fanned out down the side streets. The synagogue was probably looted and set ablaze immediately, as the town’s inhabitants were violently dragged out of their homes and hiding places with mechanical efficiency. Most homes and major structures were either demolished or burned to the ground in the ensuing hours. According to Paul W. Ginsburg, in his website “www.sudilkov.com”, the victims were then herded into the ghetto of neighboring Shepetovka. He relates, The Jews in the

ghetto of Shepetovka were executed in three stages in the forest on the road to

Klementovichi. These executions

took place on July 21, 1941 (26 Tamuz 5701), June 20, 1942 (5 Tamuz 5702) and

August 10, 1942 (27 Av 5702). Many

Jewish houses in Sudilkov were destroyed after the Jews were deported to the

ghetto in Shepetovka. The Jewish

cemetery was also destroyed and grave stones from the cemetery were stolen by

the local citizens for use in constructing the foundations of their future

houses. Today there are no Jews in

Sudilkov. Arad Yitzak, Shmuel Krakowski and Shmuel Spector, in their book The Einsatzgruppen Reports (New York, 1989), published English translations of the progress updates which were meticulously drawn up by the captains of the mobile killing squads for their superiors in Berlin. One of the documents, entitled “Operational Situation Report USSR No. 38” and dated July 30, 1941, was written by the Chief of the Security Police and the SD of Einsatzgruppe C. In part I, labeled “Activity Report”, the chief recounts the operations underway in his assigned area of the occupied territory of “Russian Poland”. He writes: “At the time of [this] report, another 416 persons, most of them Jews, were shot because of Communist activity, such as Communist commissars in the Red Army, murderers of Ukrainians who had nationalistic views or as agents of the NKVD. More than 1,000 persons were arrested because of similar offenses or for looting, gang-raids, etc. “The offices of the party committees, NKVD and border guard were constantly searched. Prior to their retreat, the Russians were able to destroy or take with them in some cases all of their documents. Some of the files and maps were seized and are still being evaluated. A gun repair shop of the NKVD with 1,000 guns, 2 H.M.G.’s, and 70 boxes with ammunition, was discovered in Lvov and removed. The searches for NKVD agents are becoming more and more difficult as they are constantly changing their quarters. “15 persons were arrested in Lvov because of activity as part of the Polish terrorist group ZWZ. With the arrest of NKVD agent Sekunda in Lvov, assistant to the well-known captain Orlov, the names of persons who had been sent as spies into the General Gouvernement after special training were revealed.” In part II, subtitled “Situation Report”, the chief is preoccupied specifically with the Jews: “Behavior [of the Jews] continues to be offensive and provocative. In the rear areas, some of the Jews who had fled are returning. Illicit trading is stopped, markets in smaller towns are full of Jews hoarding. A ‘Jewish Community’ has been established in Lvov by an official order. Their task: taxation, registration of Jewish population, and organization of social self-help.” In the third and final section of the document, the chief reports on the progress of Einzatzgruppe C in the area of Zhitomer, which would have included Sudilkov: “Arson is still frequent. In agreement with General Reinhardt and with German Army support a major action was carried out which ended with the arrest of 200 Communists and Jews. After having established the personal data and examining the cases, 180 Communists and Jews were shot. The interrogations have again shown that, like in other towns, the important personalities are no longer there. It is, however, possible that for the time being, Jews in particular remain in hiding in the surrounding areas of the town. They will be caught when the villages are systematically searched in the near future...” Here we learn of the commander’s specific intention to hunt out Jews in the region around Zhitomer, the old capital of Volhynia. Sudilkov was certainly one of the “villages” that was “searched” by the killing squads under his command. He continues: “According to a report of EK 4a constant sabotage activity is going on in Zwiahel (Novograd-Volynskiy). The German Army now drives all the civilians together and, as retaliatory measures, carries out executions. In cooperation with the German Army and the Ukrainians, 34 political commissars, agents, etc. were plucked from civil-prisoner camps. In the meantime, they have been finished off. Two of them pretended to have important information about an arms cache in the forest. However, it became obvious on the way there that the two Russians intended to deliver the Kommando into the hands of the Russians and that they did not mean to locate the cache at all. Thereupon the two were shot on the spot. A short time later, we could observe about 100 Russians fleeing hurriedly into the forest. On the march back, a large arms cache was actually discovered. “In Proskurov [later Khmelnitsky, located not far south of Sudilkov] the entire documentation is either destroyed or removed. All officials have disappeared. 22 political prisoners were found dead, they were obviously starved in a cellar. Many Ukrainians and Poles have been deported. “Considering the situation, the relationship of Volkdeutsche [ethnic Germans] towards the Ukrainians was good. There exists, however, a pronounced lack of confidence on the part of the Volkdeutsche towards the Ukrainians. This rests on the fact that they are and will be a minority in the future. “Executions: Proskurov - 146; Vinnista - 146; Berdichev - 148; Shepetovka - 17; Zhitomir - 41; Khorostov - 30. In this last place, 100 Jews were slain by the population.” As I stated above, Shepetovka was less than 10 kilometers west of Sudilkov. Its prewar Jewish population was 3,916 (according to Moiseevich; they currently number in the hundreds). The 17 executions carried out in that town occurred on or near the day of the chief’s report, July 30, 1941, and represent only a small fraction of the Nazi atrocities committed in that community. In the succeeding days and weeks Einsatzgruppe C doubtlessly murdered thousands of Jews in Shepetovka alone, before striking out into nearby towns such as Sudilkov. Shepetovka was retaken by the Russians under General Vatutin in February, 1944. The German Sixth and Eighth Armies were swiftly driven west with the Red Army on their heals. By the end of March, Stalin’s forces were rolling across Poland towards the German frontier. Unfortunately, liberation came too late for the Jews of Sudilkov, as it did for most Ukrainian Jews. If any Sudilkovers had evaded the mass executions of 1941 and 1942, they were almost certainly captured and killed in the months preceding the German retreat. On page 285 of her 1997 book Weiner published an English translation of an excerpt from what she calls the “Sudilkov Memoirs”. These memoirs consist in nine notebooks written by the father of a woman named Zinaida Samuelovna Sandler. They contain much invaluable information on the town’s pre-war Jewish community. The following is the excerpt: During the Nazi invasion (1941-1945),

virtually the entire Jewish population of Sudilkov was destroyed.

Only a few emigrated and a few still live in Shepetovka or other cities

in Ukraine. Other survivors were

young people who were in the army during the war and did not die.

All citizens of Sudilkov were held by the Germans in the Shepetovka

ghetto, located in the region near the synagogue.

Only two girls escaped from Sudilkov: Fanya Pugach and Klara Korol.

The houses where Jews once lived are destroyed now, the cemetery is

ruined, and stones from the cemetery were stolen by local citizens for the

foundations of future houses. Only

a few remaining monuments remind us about the Jews of Sudilkov. Short of an exhumation, it is impossible to determine how many of the town’s Jews were interred in the mass grave which was hastily excavated on the edge of town. Both Berovich and Moiseevich affirm that according to the 1939 census there were 1,842 Jews in Sudilkov. We must accept the fact that very few if any could have fled in time, not only because no one had expected a German invasion, but once war broke out it was extremely difficult to leave the Soviet Union. In my correspondence with American descendants of Sudilkov residents I was never informed of anyone immigrating from there after the 1920s. After the war only one Nazi was ever punished for his role in the murder of Sudilkov’s Jews. His name was Engelbert Kreuzer. In his website Ginsburg recounts the crimes of the man he aptly refers to as the “Butcher of Sudilkov”. German War Crimes Trial Records document the role of Engelbert Kreuzer (Company Commander of Reserve Police Battalion 45) in the massacre of 471 Sudilkov Jews on August 21, 1941. In April 1969, he was brought before a German court for his participation in war crimes in Sudilkov, Shepetovka, Slavuta, Berditchev, Viznitza, Kiev, and Khorol. In 1971 Kreuzer was sentenced to only seven years in prison for his participation in these massacres. In his book Ordinary Men, Christopher R. Browning gave the following background history of the activities of Reserve Police Battalion 45: “Postwar judicial interrogations in the Federal Republic of Germany, stemming from scant documentation, uncovered further information about the murderous swath Police Battalions 45 and 315 cut across the Soviet Union in the fall of 1941. Police Battalion 45 had reached the Ukrainian town of Shepetovka on July 24, when its commander Major Martin Besser, was summoned by the head of Police Regiment South, Colonel Franz. Franz told Besser that by order of Himmler the Jews in Russia were to be destroyed and his Police Battalion 45 was to take part in this task. Within days the battalion had massacred the several hundred remaining Jews in Shepetovka, including women and children. Three-figure massacres in various towns followed in August. In September the battalion provided cordon, escort, and shooters for the executions of thousands of Jews in Berditchev and Vinnitsa. The battalion's brutal activities climaxed in Kiev on September 29 and 30, when policemen again provided cordon, escort, and shooters for the murder of over 33,000 Jews in the ravine of Babi Yar. The battalion continued to carry out smaller executions (Khorol, Krementshug, Poltava) until the end of the year.” The following information about the massacre in Sudilkov was brought to light in the war crimes trials against Engelbert Kreuzer in April 1969: “The German Reserve Police Battalion 45 stationed in nearby Slavuta perpetrated one of the first massacres of Sudilkov Jews. “On August 21, 1941, the Battalion Commander Martin Besser, ordered Company Commander Engelbert Kreuzer to round up the Jewish population of Sudilkov. Kreuzer and his men rounded up 471 men, women and children. The victims were transported to a large bomb crater about 20 kilometers outside Sudilkov. “(In the 1969 trial, a member of the Reserve Police Battalion 45 named Behmel testified against Kreuzer.) When Behmel arrived at the bomb crater, there was a woman sitting on the edge of the crater crying. Kreuzer ordered Behmel to shoot the woman in the neck. Behmel was taken aback by this order. He followed Kreuzer to the edge of the crater and saw that the crater was filled with Jews who had been shot by the Germans. During the previous round of executions, the woman had fallen into the crater without being hit and afterwards climbed out. Kreuzer once again ordered Behmel to shoot the woman. Against his own will, Behmel killed the woman. Her body fell into the crater for the last time. Kreuzer called Behmel a coward and ordered one of the drivers to take the rifle away from him. “During the war crimes trial against him, Kreuzer never further explained this allegation by Behmel and denied that he would have ever given such an order. Kreuzer's testimony was contradicted by another member of Reserve Police Battalion 45 named Galle who admitted to haven taken part in the massacre of Sudilkov Jews and witnessed the above mentioned sights. “A German record dated August 21, 1941 further documented the fact that 471 Jews from Sudilkov were executed. (In his testimony Behmel stated that there were between 200 or 300 Jews. Kreuzer, in his testimony, explained that it was common practice to inflate the number of executions in reports to headquarters.) “In testimony

during the war crimes trial, Besser, the Battalion Commander, did not remember

giving an order regarding Sudilkov. He

said that the individual companies would make decisions on their own to pursue

partisans and execute them. Under

further cross-examination, Besser admitted that he gave orders to individual

companies to participate in the exterminations of the Jews.” Moiseevich gives a terse, rather dry description of the mass grave where many of the Jews of Sudilkov were interred. He writes, “The Jewish mass grave was established in 1941. The last known Jewish burial was 1941. No other towns or villages used this mass grave. The mass grave is not listed and/or protected as a landmark or monument. The mass grave location is urban, located on flat l, marked by signs or plaques in local language. The marker mentioned the Holocaust. It is reached by crossing private property.

Alleyway leading to the mass grave at Sudilkov The access is open with permission. The mass grave is surrounded by no wall or fence. The approximate size of mass grave is now 0.01 hectares. No stones were removed. The mass grave has no special sections. Stones are datable in the 20th century starting in 1946. The mass grave has only common tombstones.

Location of mass grave The mass grave contains marked mass graves. The present owner of the mass grave property is private individual(s). The mass grave property is now used for mass burial site. Properties adjacent it is agricultural. The mass grave is visited rarely by local residents. This mass grave has not been vandalized. Now there is occasional clearing or cleaning by individuals. Within the limits of the mass grave there are no structures. Vegetation overgrowth is not a problem. Slight threat: pollution, vegetation and vandalism.” The fact that a number of tombstones have subsequently been placed on the site is a sure indication that some relatives of the town’s inhabitants survived the mass execution, either because they had emigrated before World War II or had been inducted into in the Red Army before the Holocaust began. Apparently, at least some of the former residents returned from hiding, exile, or the Russian armed forces, and placed tombstones on the grave as early as the year after the German surrender. Since the site is in such a neglected state, we can assume that these visitors have either passed away or moved to distant places. I found no evidence that any Grossmans ever returned to Sudilkov in order to place a grave marker or for any other reason. Ginsburg made a trip to Sudilkov in July, 2001 and made a terrifying discovery: Jewish Sudilkov had not vanished. I learned during my last visit that there are three mass graves in Sudilkov. Only one site has a memorial. This memorial was in someone's backyard, hidden from the world. To get to this memorial we walked across the main square and across the vacant lot that once was the Jewish market. We continued to walk straight down a dirt alley to homes that once belonged to Sudilkov's Jews. An elderly Ukrainian woman, who had witnessed the killings, showed us to the memorial. We entered through the gate and went around the corner to the backyard. The backyard was full of loose limbs, rotten wooden beams, and other debris. All this needed to be cleared out in order to access another wooden gate on the other side of the yard. We entered into a small courtyard where we could see a small memorial with a Yiddish plaque. The memorial and courtyard appeared as though no one had visited in over a decade. The Ukrainian woman provided us with a wet cloth so we could read the inscription that was covered under a layer of dirt. Then, she explained what had happened in this place. Germans and Ukrainians took the Jews of Sudilkov—all of whom were too old or unable to walk to the ghetto in nearby Shepetovka—to this courtyard. There they dug a pit into the earth and buried Sudilkov’s Jews alive. The Ukrainian woman told us that when the pit was covered, the earth continued to move for days because beneath the ground people still struggled for life. Jews who knew of the atrocity erected this tiny memorial after the war, and the Ukrainian family who took the Jewish house dutifully maintained it. The family continued to maintain it despite persecution by the Communist authorities for tending to the “Jewish” memorial. Today the son of the Ukrainians who cared for the memorial is too sick to properly care for it. At this memorial, I discovered why I came to Sudilkov. If my great-grandfather had not left Sudilkov before World War II to begin a new life in America, he may have perished there during the Holocaust. My father would have never been born, and I would not be alive. It was too much for me and both my wife and I broke down. The Jews of Sudilkov did not disappear into thin air. They were here in front of me, buried alive by their neighbors and German murderers. The horror of this place has never before been told. The story of what happened here remains trapped in a Ukrainian backyard blocked by debris. Sixty years later, it is too late to avenge these people. I can only tell the world their story, internalize it, and pass it on to the next generation. I now understood the purpose of my visit to Sudilkov. My journey came full circle. To walk away from this place unchanged was impossible. The Rabbis of the

Talmud said, “Every person in Israel is required to ask: When will my deeds

reach the deeds of my forefathers?” By leaving Sudilkov, my great-grandfather

had given me life. To me there

could not be a greater hero. I can

only pray that I will live up to his legacy. In his website Ginsburg documents a mysterious photograph attached to the memorial plaque at the site of the mass grave. He does not know whether the man represented was a victim of the massacre or the person who commissioned the plaque.

Mass grave memorial picture David A. Chapin recently visited Volhynia and north Podolia in order to learn about the region where his grandparents were born. The autobiographical account of his trip, posted on the website of the Dallas Virtual Jewish Community in May, 1998, gives us more of an idea of the tragic fate of Ukrainian Jewry in the aftermath of the German invasion. He writes: We passed through Zhitomir and Berditchev, both of which struck me as modern, grimy cities. Then we went to Letichev—the town where my grandparents were born. Nothing is left of the old Letichev of my grandparents. The old castle has only one tower remaining, and the Ukrainian church was recently restored, but that was about it. All of the houses I saw were built very recently, many in the last 20 years. I visited my friend Evgenia Tretyak, who had exchanged letters with me for several years. She and six others were the last remaining Jews of a town that once had more than 7,000 Jews making up more than 50% of the population. We met with all the Jews of the town and went to the Nazi mass killing site. Letichev sits astride the main road between Proskurov (now named Khmelnitsky) and Vinnitsa. During World War II, Vinnitsa served as headquarters for the German Army and, for a short time in 1942, Hitler lived there in a bunker code-named Werewolf. In order to supply Vinnitsa and points further east, Albert Speer’s Organisation TODT, a paramilitary engineering unit, rebuilt the main road. Letichev served as a slave labor camp for the road-building project. While the Jews in other towns in that area were marched to the edge of town and shot, the Jews of Letichev were kept alive into 1943 to help build and maintain the road. Thus there were a few survivors of this ghetto. In the end, the ghetto was liquidated and nearly 7,500 Jews were killed in a ravine south of the town. It was this spot that our strange entourage visited...

Khmelnitsky is the home of a large archive, which was once the

headquarters of the KGB records for the Oblast. This archive is modern and well

indexed with available photocopy equipment.

It primarily contains records after the Russian Revolution of 1917. I

found some interesting enrollment records from the Jewish elementary schools in

Khmelnitsky Oblast [which includes Sudilkov].

I also found lists from the Soviet Extraordinary Commission which

attempted to document those killed in the various Nazi mass killing sites. I included this last paragraph of his essay in order to urge anyone with the time and funds to go to Khmelnitsky and search the public archives there. In spite of Weiner’s failure to find documents on Sudilkov, it is possible that there are still resources to be investigated, such as the Khmelnitsky archive. Perhaps there are records there of Grossmans attending Jewish elementary school! With regard to the mass execution in Sudilkov, I recently was made aware of some facts which are as precious as they are significant. In an Email of November 25, 1998, Weiner wrote me the following: “Hi, I just remembered something I could check quickly. Someone prepared a listing for me of Jewish residents of Sudilkov (probably around the time of the Holocaust) which includes the following Groisman entries: First family: Shmil Groisman (a rich man), his wife, sons: Dudya, Josef and Ruvin; daughters: Tekha and Fanya. Second family: Nusin Groisman. Third family: Duvid-Leib Groiserman (a butcher), wife Raizel, daughters: Serka, Ida, sons Gdali and Avrum. According to the person who prepared the list, these people were killed in the Holocaust: Duvid-Leib, Raizl, Avrum; Shmil’s wife, all children. I don’t know if these names mean anything to you. I have absolutely no further information about any of these people other than their names on a list. The person who prepared the list has died. This is the only help I can give you at this time. Note the Groiserman spelling above. It is spelled as it appears on my list.” As I stated in the first chapter, “Groisman” and “Groiserman” are both pronounced “Grossman”. This is the only evidence I have discovered that Grossmans still lived in Sudilkov at the time of the Second World War. As Weiner indicates, there were two Groisman families and a Groiserman family on the eve of the Holocaust. They were all murdered except for Shmil (who lost his wife and all his children), Nusim (who seems to have never married) and three of the children of Duvid-Leib and Raizel (Serka, Ida and Gdali). Thus, there were five survivors in all! If Nusim and Gdali subsequently had any children it is possible that the “Groisman” and “Groiserman” names survive somewhere, perhaps as “Grossmans” in the United States or Israel. We can be reasonably certain that these people were indeed our European relatives. Sudilkov was too small to have had many different Grossman branches. We must bear in mind that our ancestors left only fifty years before the war, leaving behind a number of relatives, including Leah, who may have had Grossman cousins (who then had children). As for the five survivors, one can only guess how they managed to escape from the Germans. It is important to note that there is no certainty that Weiner’s list is complete. In fact, we must not rule out the possibility that that there were other Grossman survivors. Especially interesting is the fact that Duvid-Leib was a butcher! Moishe Grossman, twenty years after arriving in the United States, set up a butcher shop on North 5th Street in downtown Minneapolis. Perhaps he had chosen the occupation which he knew best from his past experience in Sudilkov. It is even feasible that he worked for Duvid-Leib’s grandfather at the butcher shop in his home town before emigrating in 1890. We Grossmans may have been a family of kosher butchers in the old country, as Moishe and Temma were in downtown Minneapolis. Of course, this is all speculation, but if we take into account that European men almost always went into the family business, it does not seem so improbable. Indeed, it seems likely. In the course of my research on the Internet I compiled a list of all the names I discovered of Sudilkovers who immigrated to the United States. They are the following: Friedman, Karass, Kemelmacher, Kerzner, Kimel, Kniznik, Leimberg, Lerner, Schluger, Schwartzman, Vilkhov, Weiner, Winicor, Winiker, Winiku and Winocur. I expect this list to grow during the next several years as I expand my contacts with other researchers. Many other names could potentially be gleaned from the Sudilkover cemeteries in Boston and New York mentioned above. |