|

|||

|

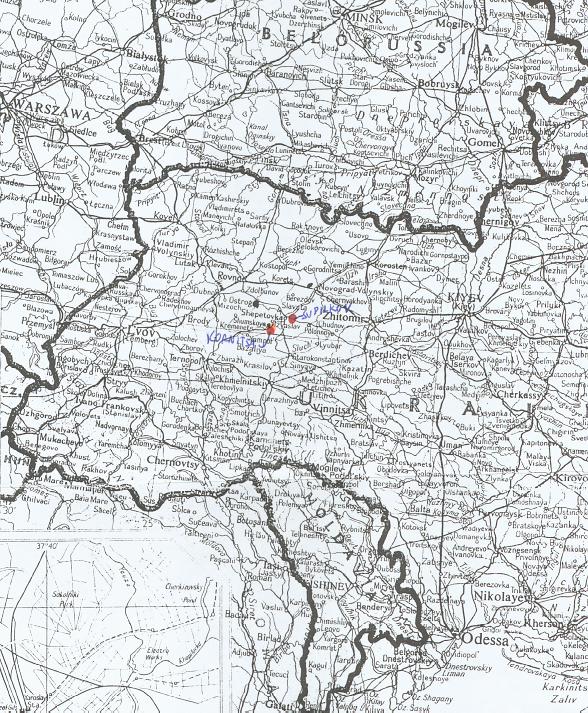

The history of the Grossman family would not be complete without taking into account the Biermans and their relatives the Bermans. As I suggested above, there existed a special relationship between the Grossmans and Biermans in Volhynia Gubernia. For reasons which remain mysterious the two families intermarried several times, not only in the Old Country, but in Minneapolis! We can only guess that the first Grossman-Bierman wedding induced a kind of chain reaction. Young Grossmans and Biermans were introduced to each other by their older relatives and marriages were arranged by the family patriarchs. The Bierman family came from the shtetl of Kornitsa (also spelled “Kornitza”), located a short distance to the west of Sudilkov.

Positions of Kornitsa and Sudilkov Actually, I managed to locate

three shtetls in Eastern Europe carrying the name “Kornitsa”: one was in

Bulgaria, 73.8 miles SSE of Sofia; another was in Belarus, 105.4 miles north of

Minsk; and a third was in Ukraine, 177.9 miles west of Kiev, at coordinates 26°

32 longitude by 50° 03 latitude. These coordinates place the “third” Kornitsa right near

Sudilkov, which, as I already stated, was situated at 27° 08 longitude by 50°

10 latitude. Given the marriage

This is the sum of what I had been able to gather on Kornitsa—that

is, until I contacted Sally Tofle of St. Louis, Missouri via Internet.

Sally and another woman, Bernice Marcus, organized a conference on the

Ukrainian communities of Yampola, Kornitsa and Lacherwitz (now “Belogorye”

or “Beligira”) which took place on November 10, 1996.

According to Reeder, Lacherwitz, Yampola and Kornitsa were close

enough to one another geographically that they more or less shared the same

political history. Lacherwitz became a town of consequence when the Polish built a major fort there sometime between 1500 and 1600. It was a wooden structure in the form of a circle and was surrounded by mounds of earth. In that period the town below was transformed into a kind of trading post for merchants traveling between Poland, Turkey and Russia. The surrounding region was agriculturally very productive, and foodstuffs were exported all over Eastern and Central Europe. On the strength of its vigorous export industry and international commercial activity Lacherwitz grew to be very wealthy. In 1583, in order to increase economic development, Lacherwitz was granted special privileged status under the Magdeburg Law. Thenceforth, instead of levying taxes on individual citizens, the town was made to pay a single collective tax. In 1622 the Dominicans built a major establishment there, while the Protestant movement spread throughout the area. By the time of the Cossack Revolt of 1648, Lacherwitz, Kornitsa and Yampol had collectively become an important center of Jewish learning. Lacherwitz had a yeshiva, several Jewish schools and a printing shop for reproducing Hebrew texts. The 1648 revolt and the war that followed saw the destruction of Lacherwitz, Kornitsa and much of Volhynia. Tartar mercenaries burned down these and many other towns, including nearby Zaslov and Mazineth. The situation worsened in 1664 when the Protestants and Catholics began an armed struggle which further devastated the three communities. At that time there was a general anti-Semitic persecution which forced Jewish schools, including the yeshivas, to go underground. By 1686 there were only 250 buildings left standing in Lacherwitz and Kornitsa, and not many more in Yampol. Just as the residents started to rebuild, Sweden launched a major war against Poland and Russia, wrecking havoc on the entire region. In 1744, the magnate Zancuschka, who owned all of the land in the region, built a large fortified residence in Lacherwitz which included a great library. By that time the population of the town was down to around 400 families. In 1765, there were 589 Jews in the town, 49 in neighboring Kornitsa, and another 220 scattered about the surrounding countryside. We can reasonably assume that by this time the area was predominantly Jewish. However, Reeder argues that although there was a high proportion of Jews in the population, Lacherwitz and its two neighbors were hardly typical shtetls. This was because the Jews lived side by side with the gentiles. In 1848 a cholera epidemic swept through the region and took the lives of many of the three towns’ inhabitants. This disaster was followed by a series of typhoid plagues between 1872 and 1893. In 1860 the government built the first non-Jewish school in the area and tried to pressure the Jews to attend, but it was later closed. The 1873 census indicates that Lacherwitz had 1,422 inhabitants, 353 of whom owned farms in the surrounding countryside. In 1883 and 1899 major floods submerged the entire region, while the years 1890-1892 saw a terrible drought. In 1884 Lacherwitz and Kornitsa had a combined population of 2,000 Jews and 800 gentiles. Aside from the flood of 1883, the two towns generally prospered in the twenty years after 1870. The region acquired its first hospital in 1890. In the same year there were also two mills, a vodka distillery, two factories and a number of smaller enterprises. The ancestors of Dwight Gold, who lives in St. Louis, owned all the mills in town. Lacherwitz was licensed to hold eight markets a year, which were vital to the economy of the entire region. The homes of the common people were made of wood and had straw roofs, while the well-to-do could afford tin roofs. Toward the end of the century Jews were beginning to emigrate in large numbers because of economic crises, health problems, and especially the pogroms. The “Evreiskaia Entsiklopedia” reports that in 1897 there were only 517 Jews left out of 1,251 inhabitants, about 41% of the total population. The people of the region, including many Jews, supported the Social Democrat Kerensky, which caused them to fall out of grace with both the Bolsheviks and the czarist forces. By November 1920 Volynia was firmly in the hands of the Russian communists. Under their rule the three towns were made the center of the sugar beet industry. The First Five-year Plan and Second Five-year Plan called for the creation of a peat business, furniture factory, and chalk and brick manufacturing plants. In 1927 a 20-bed hospital was built, later expanded to 70 beds with three resident doctors. Finally, in 1940 a large tractor and combine factory was completed. The Jews who did not emigrate by World War I were massacred by the Nazis together with their children in July, 1941, along with numerous ethnic Russians and Ukrainians—3,000 in all. They were lined up in front of a ravine in the Trotschameski Forest and shot. Many of the victims were Jewish resistance fighters. Dozens of others were executed on 27 June, 1942. Another 180 young men and women were sent to a labor camp from which few if any returned. In Lacherwitz the local school was converted into a horse barn while the cinema and other major buildings were burned. The year after the war the name of the town was changed to Beligira. In the local

cemetery there is a monument to the victims of Nazi atrocities which consists of

three headstones. An inscription on

the left stone reads, “For our dear relatives and friends who lived in Yampol,

Bilgorye, ----, Kornitsa who were murdered by Nazis on the 27 June 1942.”

The center headstone states, “Here are buried 3,000 residents from

Yampola, Kornitsa and Lacherwitz. The

wild animal has murdered our people. The

living will never forget you. June

27, 1942.” The right headstone

was erected by a Jew named Schmoith from Kornitsa who, after having remained

abroad during the war, returned to discover that his entire family had been

murdered. It is inscribed with the

words: “Here are buried Jews who were murdered by Nazis on July 27, 1942.

Father Schmoith SM 1898-1942

Mother Schmoith AB 1904-1942

Sister Schmoith SS 1922-1942

Brother Schmoith DS 1933-1942”. Evidently,

Schmoith mistakenly substituted the word “July” for “June”.

Sally sent me xerox copies of photographs of the left and right

tombstones. Reeder claims that every October or every other October, for years after the war, survivors and their friends and relatives, including a handful of Jews, gathered from around the Soviet Union to visit the monument. Only three Jews currently live in Lacherwitz, none in Kornitsa. They are a woman, her son and her sister. While interviewing one of the two ladies in September, 1993, Reeder learned that no Jews from the West and nobody from Israel had ever come to visit the area, and the locals never understood why. By coincidence the sisters’ grandfather once worked for Reeder’s great-grandmother Chaya Ruchel Litvanchuk Fellman (Fierman) in their family tavern in Lacherwitz. Although now covered in white stucco and tile, the building still survives and is known as “the Jews’ Bar”. Like Lacherwitz, Yampol became rich by the early-seventeenth century. Its economy also benefited from the Magdeburg laws. Eventually the town surpassed both Lacherwitz and Kornitsa in economic importance. In 1616 Yampol was licensed to hold a market every Thursday. By the eighteenth century the inhabitants had developed strong financial ties with Russia, Poland, Lithuania and Turkey, exporting agricultural produce in all directions. Towards the end of the century the town began to engage in the manufacture of fine rugs. Unfortunately, much of the progress which had been made was wiped out in the course of the Napoleonic Wars, especially when French troops passed through town in 1805. In the nineteenth century Yampol prospered from of its brewery, vodka distillery and sugar beet industry. To this day these are the principal industries in the region. By the late-nineteenth century Yampol, with a total of 33 stores, was by far the richest of the three towns. There is currently a small number of Jews still living in Yampol. Unfortunately, Reeder did not have the opportunity to visit there. The name “Kornitsa”, unlike “Lacherwitz”, was never changed in the course of the centuries and always retained the same pronunciation. The two communities were only 4 to 7 kilometers apart, and one could easily walk between them in less than an hour and a half. Yampol, by contrast, lay 30 kilometers to the southwest, and although it was not far away by Russian standards, it was still a half to full-day trip by foot. The town of “Old Kornitsa” vanished sometime during the era of the Tartar invasions in the thirteenth century. It was located on a little hill capped by a monastery, about two and a half kilometers west of the present community, “New Kornitsa”. It probably lay on the exact site of the “ben Kalika Mill”, next to which a clear spring bubbles, the greatest natural asset of the once-thriving settlement. Old Kornitsa was apparently rebuilt and destroyed several times since the Tartar invasions before it was finally abandoned in favor of the present site. This occurred at some undetermined moment well before the Biermans emigrated to the United States. According to Reeder there was a saying among the locals of the area: “One day there is Kornitsa. One day there is not. They take the sign down and they put it back up again.” A farmer living in a house near Old Kornitsa once dug up an antique silver plate. Every so often other objects are discovered a few feet beneath the soil. According to Reeder there has been much speculation about Old Kornitsa’s origin as a Jewish settlement. She reports that during World War II a major in the British forces by the name of Maurice Davies showed up on the doorstep of her Rothman cousins who lived in America. He was on General Eisenhower’s staff and was helping plan the invasion of Normandy. On an official trip to the United States he went out of his way to pay a visit to the Rothmans because his mother’s aunt was Reeder’s grandmother. On that occasion he told his American relatives of the research he had been carrying out on Kornitsa since before the war. Although he could not prove it, he concluded that at the time of the Spanish Inquisition a group of Spanish Jews, led by their rabbi, fled across Europe to Volhynia. Upon their arrival, the rabbi used his influence and connections to forge an agreement with the local Zancuschka magnate to lease land by the river Goryn in a place called Kornitsa. In return for his efforts the rabbi was made head of the community and his family was given control of the mill. This was the legendary ben Kalika family, and its members served as the titular leaders of the town all the way to the time of Alyamida ben Kalika. The latter left Kornitsa in the early 1920’s and took up the name Rothman when he emigrated to the United States. He was the maternal grandfather of Marty and Ray Pultman, who were present at the above-mentioned conference in St. Louis. Similarly, the Zancuschka magnates, who had resided in Volhynia since the Middle Ages, owned the land in and around Lacherwitz and Kornitsa until the Russian Revolution, when the Communists stripped them of all their possessions. Reeder’s grandmother, Rissel Leah Radizwill, who owned the land just north of the Zancuschka estate, married a man named Alcunin Fellman; the latter’s mother was Chaya Ruchel, the owner of the above-mentioned bar in Lacherwitz. Reeder claims that the Spanish Sephardic origins of the community set it apart from Lacherwitz and Yampol. The Jews of Kornitsa tended to keep to themselves, while maintaining many of their ancient traditions. Reeder affirms that many of the Jews who came from Kornitsa had fair skin, light hair, and blue or green eyes, as did many of the people attending the conference in 1996! They did not much resemble their Jewish brothers in neighboring Lacherwitz and Yampol. Sally Tofle did some additional research on her own and discovered that historical documents confirm that several towns in Poland were founded by Sephardim in the time of the Inquisition. The town of Zamosc is one example. According to Alexander Beider’s book on the history of Jewish names in the Russian Empire, the surname “Chazen” or “Hazzan” was especially common among Sephardim. In fact, many St. Louis Chazens hail from Kornitsa. On a fascinating note, John Marcus told me that his mother Sophie Marcus (daughter of Jacob Dov Berman) told him several times that the Bermans were descended from Jews escaping from the Spanish Inquisition! Evidently, this information had been passed down from Berman to Berman for generations. As incredible as it may seem, John Marcus and his siblings are probably the last people alive who still carry this knowledge—that is, before its inclusion in this essay! As Reeder suggested above, the political history of Kornitsa up until the nineteenth century was basically united with that of Lacherwitz. However, in the last two decades of the 1800s a few interesting details distinguish Kornitsa from its larger neighbor. The actual town where the Bermans once lived was in fact New Kornitsa, since Old Kornitsa had long since been abandoned. New Kornitsa was a circular town with a church in the center, a synagogue, a school, and a town hall flanked by a high minaret-like tower. The latter, very similar to the one in Lacherwitz, had been built by the Zancuschka magnates. In 1883, only a few years before the first Bierman fled to the United States, the Jewish population of Kornitsa stood at about 600, with an additional 400 non-Jews. The town had precisely ten stores and hosted a few major markets each year. Sometime before 1900 the ben Kalikas built an impressive new mill in Kornitsa which had three wheels. Most of the town inhabitants either worked as tradesmen or made fishing nets for the fishermen who plied the Goryn River, which passed right through the town. During the last week of September, 1993, Perri and her cousin Roz Fellman Wolfe traveled to Ukraine in order to visit what is left of the communities of Lacherwitz and Kornitsa. They were probably the only American Jews ever to have done so. Preliminary work included making sure they were headed for the right location, for there are no less than seven towns named “Lacherwitz” in Russia, Ukraine and Poland! Once they got their bearings straight they took a train from Kiev to Lvov, which was the nearest city to the region they intended to visit. It was a 36-hour trip in a run-down train without heat. At the many checkpoints where their documents were checked by armed guards they pretended to be Christians looking for the grave of their great-grandmother, in order to allay any suspicions the guards might have had about two American women wandering around alone in the middle of nowhere. They wore babushkas and carried around a photograph of a cemetery with a cross, pointing to it and telling everyone they met, “Looking for great-grandmother!” Using this stratagem the two were treated with great sympathy by just about everyone. They were offered tea by the military and hugged by the locals. Once in Lvov, they met a Ukrainian family from New York that was on its way to put up a cross in a cemetery where their relatives were murdered in World War II. The family helped Reeder and Wolfe find a bodyguard to accompany them, and the guard in turn arranged for a driver and an interpreter. A this point the five of them set off by car for Rovno and then Kremenetz. Driving east from Kremenetz they passed through a restored “historical section”, which is a region where people still live in traditional wooden houses with straw or tin roofs. These houses are of the type once inhabited by Jews in the nineteenth century. When they arrived in Lacherwitz (now “Beligira”) they found that little had changed since the time their ancestors emigrated a century before. Barnyard animals still wandered in and out of the houses, which all had dirt floors, even the modern ones. Flocks of geese crossed the unpaved streets which still had open sewers running down the middle of them. There were no cars. When they ran out of gas they were forced to pay US $160 for ten gallons, since only contraband was available. Reeder managed to find the building which had once been her great-grandmother Chaya Ruchel’s bar and home. Aside from an apartment building it was still the largest edifice in town! Chaya Ruchel used to bake bread in the bar’s ovens while her strongest sons would trek out to the vodka distillery to fetch a tank of vodka. Ukrainians and Russians would come in, sit down and eat the bread and drink the vodka. Chaya Ruchel was also the leading midwife in the area, and “brought in” many people into the community. Unfortunately, Reeder spent only a short time in Kornitsa. She took a photo of the bridge over the Goryn River and of the railroad crossing where Kornitsa and Lacherwitz townsfolk still go to flag down the train!

Kornitsa, River Goryn According to her, Kornitsa, like Lacherwitz, is preserved in a state of arrested development. People still get around there by horse-and-buggy. A good number of the old wooden houses are still standing, but have been covered in ugly stucco. Many of the residents are immigrants from Eastern Europe and other areas. In fact, very few native people still live there. Reeder claims that there is no longer any anti-Semitism, but then hastens to remind us that there are also no Jews. After visiting the memorial in the ravine where the residents of the two towns were executed in 1942, the two women set off in search of the old cemetery which was shared by Yampol, Lacherwitz and Kornitsa. By sheer luck they met an old lady who said that when she was young there had been a cemetery somewhere between the latter two towns, but the other locals they encountered insisted that it did not exist. Two hunters they met by the road said it still existed but that only one stone was standing. The women and their escorts drove around the area through muddy fields because there were no roads to where they were going. They finally came upon the single stone at the edge of the woods mentioned by the hunters. Next, the three escorts explored the woods until they discovered the rest of the cemetery. It was in a sorry state, overgrown with bushes and shrubs and littered with extremely old headstones, some teetering precariously, others already fallen. The Hebrew inscriptions were still legible on many of them.

Kornitsa gravestone According to Reeder, the cemetery survived the Nazi invasion only because of its remote and hidden location. On her next trip to Ukraine Reeder is planning to record the epitaphs systematically. Her ultimate goal is to have the cemetery declared a national monument by the Ukrainian authorities. In addition, she hopes to found a movement for helping the descendants of the victims of Nazism and Communism recover their ancestral land. Reeder explains that most of the Jewish inhabitants of Kornitsa who emigrated to the United States ended up on the East Coast, in Omaha or St. Louis. Alyamida ben Kalika and his family settled in the latter city. At one time there was a society in the Northeast called “Kornitsa” but it vanished long ago. The Holocaust Museum gave Reeder the names of two survivors from Kornitsa but the two did not wish to be contacted and never responded to her letters. Interestingly, Sally Tofle wrote me recently that she is researching her Chazen cousins who came from Kornitsa. She informed me that several Grossmans married Chazens there. Thus, the Biermans were not the only target of the Grossmans’ affection in that particular town! |