|

|||

|

With regard to the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries I was able to learn very little about Sudilkov, but I did find information on the major religious movements which swept through the region and, almost certainly, made an impression on the town. Ukraine produced some of the greatest scholars and thinkers in the history of the Jewish people. Without a doubt the most illustrious among them was the Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760), the father of Hasidism—a man who single-handedly inaugurated a new era of Jewish spirituality in Ashkenazic Europe. His disciples spread his teachings all around the continent while contributing important commentaries and treatises of their own.

Rabbi Yisrael Bal Shem Tov, 1698-1760 The future Baal Shem Tov was born near the Polish border in the small Ukrainian village of Okop. We know that his parents passed away when he was still a toddler and that he devoted himself to study from a very young age. In the course of his education he developed an exceptionally strong emotional relationship with G-d. This relationship came to form the basis of a religious system which ultimately matured into what came to be known as Hasidism. Through his close contacts with the local synagogue he attained an extremely high level of knowledge of all Jewish texts and in time immersed himself in the mysteries of the Kabbalah.

After his wife passed away he moved to a town near Brody where he

was employed as a teacher for young children.

The rabbi of that town was so impressed with his wisdom that he offered

the newcomer his daughter Leah Rochel in marriage.

Rabbi Yisrael (the future Baal Shem Tov) then moved with his new wife to

a small town in the Carpathian Mountains and devoted himself to study and

worship. Finally, in the year 1734,

at the age of 36, he revealed himself to the world.

He then settled in Talust where he quickly gained a reputation According to an anonymous writer for a very informative website entitled “Great Jewish Leaders”, “The Baal Shem Tov’s teachings were largely based upon the Kabalistic teachings of the Arizal (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria, 1534-72) but his approach made the benefits of these teachings accessible even to the simplest Jew. He emphasized the profound importance and significance of prayer, love of G-d, and love of one’s fellow Jews. He taught that even if one was not blessed with the ability or opportunity to be a Torah scholar, one could still reach great spiritual heights through these channels. It is important to note that while the Baal Shem Tov taught that Torah study was not the only way to draw close to G-d, he did not teach that Torah study was unimportant or unnecessary. On the contrary, he emphasized the importance of having a close relationship with a rebbe, a great Torah scholar who would be one’s spiritual mentor and leader. Furthermore, it should also be noted that while Chassidus was (and continues to be) of great benefit to the unsophisticated, it is a very sophisticated system of thought. As anyone with any experience in Jewish studies can attest, the many major Chassidic works were written at a very high level of scholarship by men who had reached the pinnacle of Torah knowledge.” At the time the Baal Shem Tov passed away, the Chassidic movement had grown to approximately 10,000 followers, but soon it came to include a “significant portion of European Jewry”. The Baal Shem Tov never set his teachings down to writing, and today we know them only because they were diligently recorded by his disciples, particularly Rabbi Yakov Yosef of Polonoye, the author of the first published Hassidic work, Toldos Yakov Yosef. The Baal Shem Tov was survived by a son and a daughter, and was succeeded as leader of the Chassidic movement by Rabbi Dov Baer, the Maggid of Mezritch. Another important figure, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Ephraim, a famous intellectual of the early-nineteenth century and a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov, is known to have been the rabbi of Sudilkov. According to tradition he was actually the Baal Shem Tov’s grandson! Hillel Zeitlin, who wrote a well-known essay entitled “The Son of Feiga the Prophetess” before he was executed by the Germans in 1942, claimed that Rabbi Ephraim of Sudilkov was the brother of Rabbi Boruch of Mezhiboth (“who conducted his rabbinate with a high hand, and who considered himself the one true inheritor of the Baal Shem Tov; his brief teachings are collected in the small book, Botzina Dinehora”) and also of Feiga, student and spiritual “daughter” of the Baal Shem Tov. Until the age of twelve Ephraim was raised by his grandfather, the Baal Shem Tov himself, and thereafter by his brother-in-law, Rabbi Avraham Gershon, who described him as a “prodigy”. Ephraim later befriended Rabbi Dov Baer, the Maggid of Mezeritch, as well as Rabbi Yacov Yosef of Polonnoye. Rokhel claims that Ephraim was so famous that “thousands of Jews from near and far were attracted to his court to hear the Torah of G-d from his lips.” He purportedly renounced worldly wealth and chose to live a life of poverty. In his last years he settled in Medziboz, where he died and was buried next to the Baal Shem Tov.

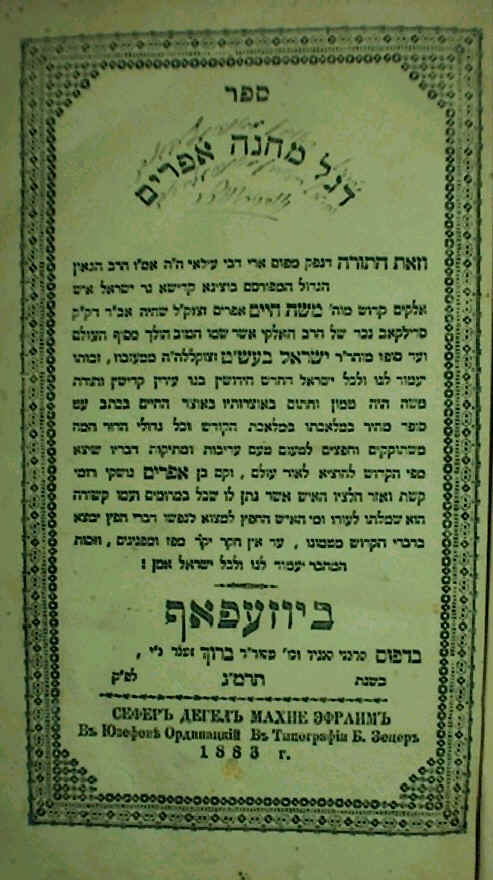

Tomb of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Ephraim of Sudilkov The fact that Ephraim was one of the only four people buried on the same plot as his grandfather is proof of his great significance to the Jewish people. His famous treatise, the Degel Machaneh Ephraim (Banner of the Camp of Ephraim), was published by his son, Rabbi Yacov Yechiel, in Koretz in 1810, and is one of the classic works of Hasidism. It has since been reprinted many times. The work not only contains his discourses on the weekly portion of the Torah, but also records his mystical “visions” from 1780-1786. He quotes the discourses he heard from his illustrious grandfather and from Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk. According to Rokhel, the book was so cherished by the Hasidic community that Ephraim was also known by its abbreviated title, “Hadegel”.

Degel Machaneh Ephraim: 1883 title page of edition printed in Yosefov, Ukraine Feiga’s husband, Rabbi Ephraim’s brother in law, was Rabbi Simcha, “one of the brilliant Torah scholars and Hasidim of his time, while her son, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, born on Shabbos Hagadol in 5532 (1772) in the town of Mezhibozh, was one of the greatest spiritual leaders of all time and the founder of the Breslov Hasidim movement. Breslov is located a couple hundred kilometers southeast of Sudilkov in the neighboring province of Podolia. One tradition insists that Rabbi Nachman was the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, which is supported by the tradition that Nachman’s uncle Ephraim was the Baal Shem Tov’s grandson. Our Grossman ancestors, Moishe and Zeesle, were born right around the time Nachman died (1810). It is likely that their parents saw him around or even knew him personally. They certainly would have known Rabbi Ephraim. Evidently, Sudilkov lay in the part of Europe where Jewish religious activity was most intense. Since Rabbi Ephraim lived in town and was closely related to the greatest Jewish protagonists of his day, all of whom lived in nearby shtetls, it is easy to imagine that these men made a deep impression on the spiritual and intellectual life of our ancestors. Indeed, it is conceivable that the Baal Shem Tov himself visited Sudilkov. It is worth delving further into the teachings of Rabbi Nachman, not only because his uncle was the rabbi of Sudilkov, but because of his larger significance for Ashkenazic Europe. The Internet site entitled “Breslov Hasidism” summarizes Rabbi Nachman’s philosophy: “The Breslov approach places great stress on serving G-d with joy and living life as intensely as possible. ‘It’s a great mitzvah always to be happy,’ Nachman taught. One distinctive Breslov practice is hisboddidus (hitbadedut), a personalized form of free-flowing prayer and meditation. In addition to the regular daily services in the prayer book, Breslover Hasidim try to spend an hour alone with G-d each day, pouring out their thoughts and concerns in whatever language they speak, as if talking to a close personal friend. Rebbe Nachman stressed the importance of soul-searching. He always maintained that his high spiritual level was due to his own efforts, and not to his famous lineage or any circumstances of birth. He repeatedly insisted that all Jews could reach the same level as he, and spoke out very strongly against those who thought that the main reason for a Tzaddik’s greatness was the superior level of his soul. ‘Everyone can attain the highest level,’ Nachman taught, ‘It depends on nothing but your own free choice... for everything depends on a multitude of deeds.’ Although Rebbe Nachman died almost 200 years ago, he is still considered to be the leader of the movement through the guidance of his books and stories. Breslover Hasidim today do not have a ‘Rebbe in the flesh,’ and each Hasid is free to go to any guide or teacher with whom [he feels] comfortable. No single person or council of elders is ‘in charge’ of the Breslov movement, and no membership list is kept.” Uman, the Ukrainian town where Rabbi Nachman is buried, still attracts large numbers of Jewish visitors, as does the grave of the Baal Shem Tov in Medzeboz. Because of Rabbi Nachman’s close blood relation to the rabbi of Sudilkov, it is reasonable to assume that the town’s inhabitants, including our ancestors, were intimately familiar with—if not followers of—his brand of Hasidism. One other great Sudilkover worth mentioning is the eminent Rabbi R. Ephraim (not to be confused with Moshe Chaim Ephraim), head of the court and teacher to many scholars in the town. Rokhel relates, “He was born in Ostrog to the distinguished Wohl family. His name is found in approbations in many books published in Ostrog, Berditchev, Slavuta and Sudilkov, for example, the Zohar, Hok L’yisrael, Hovot HaLevavot and others. Every year it was his custom to travel to Ostrog to pray at the graves of his family. In the year of his death, (5594/1834), before traveling to his ancestors’ graves as was his usual custom, he called his sons and daughters together and gave them a parting blessing - this was an extraordinary act. Indeed, he passed away in old age in Ostrog and he was buried in a grave dug next to that of the Maharsha, from whom he was descended.” We know from Berovich’s survey of Sudilkov’s Jewish cemetery that the people buried there were Hasids, but it is impossible to determine which sect they embraced, or whether they embraced more than one. I can only speculate that Berovich knew the community was Hasidic because of his interviews with Jews still living in neighboring Shepetovka. It seems unlikely that evidence from the cemetery itself could reveal anything more about the town’s religious past. According to Rokhel, “The position of rabbi in Sudilkov at the end of the 19th century [at the time our ancestors emigrated] was held by R. Motel, one of the grandsons of “Hadegel,” who was well respected and revered by his community. His son R. Yisrael succeeded him as rabbi of the town. He served for some twenty years until Soviet rule was established and the post was eliminated. Except for the spotty and incomplete information I have gathered on the history of Sudilkov and related in the preceding chapters, I have not been able to learn much else about the town. Therefore, I will skip ahead chronologically to the final moments of the community’s existence, to the period immediately following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union during the Second World War. |