|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

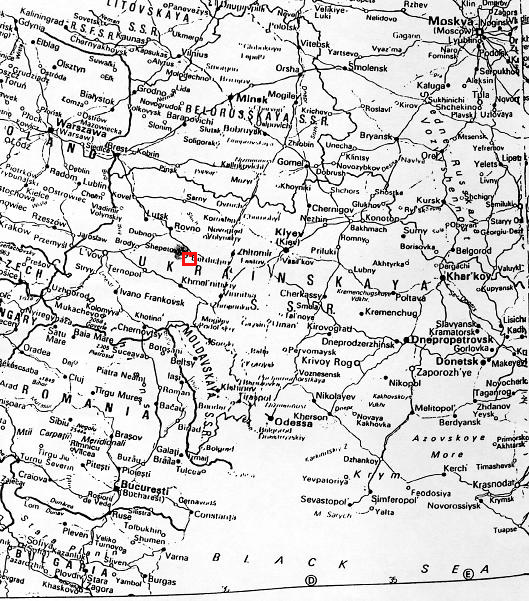

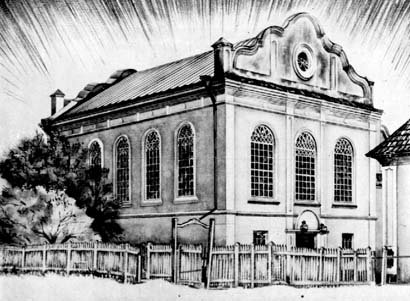

The most famous of all was the great Hasidic leader Rabbi Chaim Ephraim of Sudilkov, to whom we will return in a later chapter. For now we shall concentrate on Jewish life in Sudilkov as it existed in the era before the Russian Revolution, when our ancestors were active members of the community. A cursory glance at a map can tell us much about the social and economic realities that touched the lives of the inhabitants of the town. Given its relative geographical position within the Pale, we can hypothesize that the high concentration of Jewish shtetls in the region, the fairly close proximity of Zhitomer, Khmelnitsky and Rovno, and the presence of the railroad (from the late-nineteenth century on) greatly stimulated commercial activity in the business community. Peddlers, traders and traveling merchants linked Sudilkov’s economy to that of the surrounding region and made an impressive array of products available to the inhabitants. We can also assume that there was a constant flow of intellectual traffic through town, since students trekked great distances in order to study with eminent scholars who were living and teaching there; the reverse was also true, as scholars often went from town to town in order to spread their learning and attract followers. We know that some of the most celebrated among them stopped in Sudilkov, sometimes for extended periods. Judging by the beauty and monumentality of the synagogue, Sudilkov must have been a well-known center for spiritual and intellectual activity. Young Jewish men must have come to Sudilkov from neighboring villages in order to look for marriage partners (and vice-versa), since rural communities were often too small to meet the demand for eligibles. As we shall see, this was also true of the Grossmans, who seem to have had a special predilection for the Biermans, who lived in the nearby shtetl of Kornitsa. Only known pre-World War II photograph of Sudilkov synagogue and market

Square marks the location of Sudilkov

Because of Sudilkov’s proximity to the Austro-Hungarian frontier

and its location on the main railroad between Brody and Kiev, we can assume that

many central and west Europeans passed through town. In the absence of written sources and oral testimony it is extremely difficult to probe much further into the Jewish history of Sudilkov. We can only imagine that it was a bit larger than a simple shtetl and had a vigorous community gathered around a single synagogue. An artist’s

Artist’s rendering of Sudilkov synagogue

Kiosk on site where Sudilkov synagogue was located rendering of the synagogue, which was destroyed in the Holocaust, exhibits a large building with a single entrance and sixteen tall windows. On examination of the drawing it seems that the edifice seated approximately 300-500 people. The style of the late-baroque gable and cornice seem to date the structure to the seventeenth or eighteenth century. The presence of the round window in the facade indicates that the trusses under the roofing were exposed to the interior, maximizing the height of the sanctuary, which must have been amply lit. Pre and post-war photographs of the synagogue in neighboring Shepetovka depict a similar structure, perhaps from the same period.

Shepetovka synagogue before World War II In the pre-war photograph, broken windows and unpainted patches suggest that the Jewish community there was in decline, or at least lacked the means for maintaining the synagogue. The post-war photograph testifies to the extent to which the building was damaged in the war.

Shepetovka synagogue today One can clearly see that the Soviets botched its restoration. According to an article by Miriam Weiner in Jewish News (September 18, 1992), after the war the former synagogue had become a sports center with a basketball court. However by early 1993 the Jewish community reclaimed two rooms of the structure. I came across an interesting photograph of a man standing next to an open cabinet containing Shepetovka’s remaining Torah scrolls.

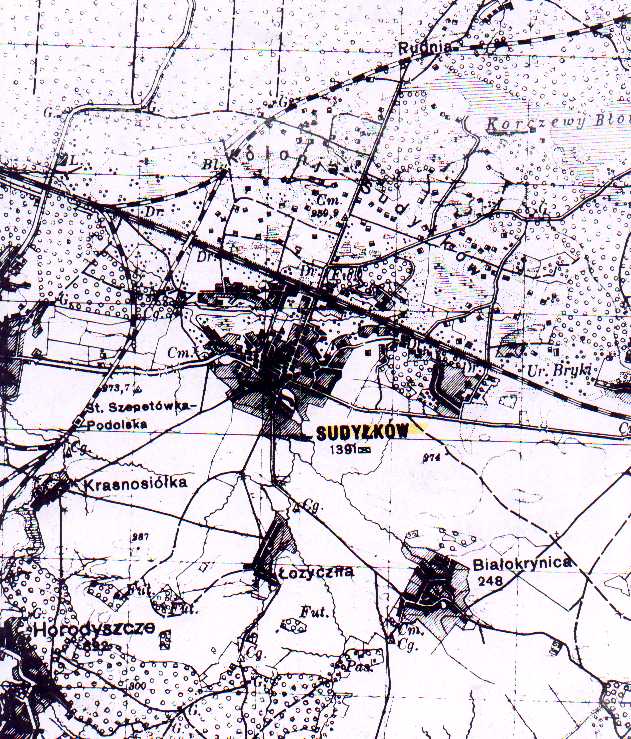

Shepetovka synagogue torahs Since Shepetovka was only 7 kilometers from Sudilkov and had a much larger Jewish community, we can imagine that our ancestors went there quite frequently. According to the nineteenth-century edition of the Jewish Encyclopedia, in 1765 only 397 Jews lived in Sudilkov. In 1847, the total population of the town (both Jews and gentiles) was 1,207. The 1897 census reveals that out of a total population of 5,551 there were 2,712 Jews. In 1939 the number of Jewish inhabitants had declined to 1,842, certainly because of emigration. Presently there are none. I was able to obtain very little information on the town of Sudilkov as it existed at the time our ancestors fled. This is due primarily to the fact that it was totally destroyed by the Nazis in 1941, who also brutally murdered the inhabitants in a single stroke. In fact, so few traces of the town survive that it is almost as if it never existed. This is, of course, exactly what the Nazis intended, but I will come back to this in the next chapter. The town archives as well as all other documentation were also lost, with the single exception of the 1900-1904 property records, stored in a government office somewhere in Ukraine. Today, only a simple road sign indicates where Sudilkov once stood. The most accurate maps of the town come from a 1931 Soviet-era document and a Nazi aerial reconaissance photograph from 1944.

1931 Soviet-era map

1944

Nazi aerial reconnaissance photo Miriam Weiner claims that in the 1920’s the Jews occupied the approximately 1,450 square meters in the very center of town. This may be an indication that Sudilkov was originally founded by Jews, since the historical center—the oldest part of the settlement—was where they were concentrated.

Central Street was once inhabited by Jews The ethnic Ukrainians, on the other hand, lived in the area around the center. Weiner claims that in 1925-1927 the Jewish quarter consisted of “Market Square”, which lay in the middle of town, nine streets and seven side streets.

A Sudilkov street One side street led directly to the railroad station. There were a total of 221 Jewish houses crowded next to one another in the center. Only five or six of the houses had vegetable gardens. Thus, there was little or no unbuilt space where the Jews lived. Weiner also claims that about 50% of the Jewish families owned small handcraft businesses, 38% were merchants and brokers of cattle, horses and agricultural produce, while the remaining 12% were professionals and employed workers. In the years leading up to 1917 there were six shoe shops, five sewing shops and two hat shops. Among the professionals were three hair stylists, three glaziers, two tin workers and two leather specialists. The local church was called Dmitriyevskaya.

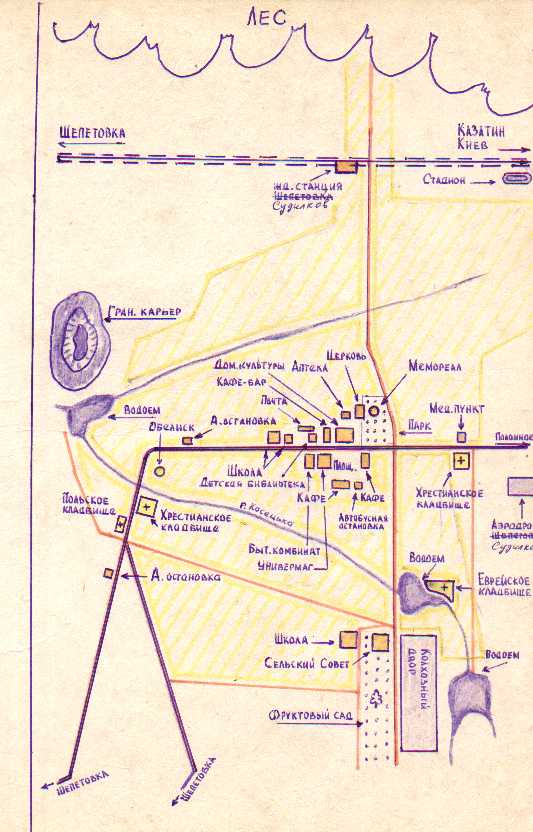

Sudilkov’s church On Ginsberg’s website there is a map of the town of Sudilkov as it existed shortly after World War II. It was created from the memory of a native who had been intimately familiar with the place. The map, which is not to scale, has recently been translated into English.

Russian hand-drawn map of Sudilkov

Stav Lake According to the map, the “Misto” was located very near the main intersection in the center of town. There the east-west road to Shepetovka intersected a less significant north-south route. In the center a number of buildings are clearly labeled: the Christian church, “Culture Palace”, pharmacy, park, stores, service center, childrens’ library, post office, school, two pubs (one named “Uncle Ivan”), a couple of bus stops, two World War II monuments and a mill. Further out from the center were the Old Christian Cemetery, New Christian Cemetery and Polish Cemetery, New School, Village Council Soviet and Collective Farm Office, Stav Lake, Shapar Lake and a huge granite quarry to the west called “Karier”. The German settlement called “Kolonia” was located on the north side of the railroad tracks, which ran from Shepetovka to Kiev. The east-west river “Gouska” passed through town just south of the main intersection while another river ran parallel to and just south of the railroad tracks. On the northern edge of the map a large, dense forest is indicated. Rokhel, who wrote his essay in 1948, provides some insight into Sudilkov’s major Jewish-run businesses and the entrepreneurs who ran them. He explains, “Sudilkov was considered as a junior partner to the Slavuta printing industry in the production of rabbinic literature. Many volumes can still be found in private collections, synagogues and libraries that were published by R. Yitzhak Madpis of Sudilkov in the beginning of the 19th century.” A man by the name of Reuven Schlenkev actually compiled a list of some of the books that were printed by Madpis, which operated from 1795 to 1939:

Unfortunately, I have not been

able to identify any Grossman ancestors in the list of names.

Rohkel continues: However, the main claim to fame of Sudilkov was its Talis (prayer shawl) manufacturing. Talitot of Sudilkov were known internationally and their production was the main source of income for the townspeople. The people of Sudilkov believed that anyone who bore the family name Talisman or Talismacher certainly could trace their origin to Sudilkov. The silk and wool threads were brought from Lodz, and in the local workshops skilled craftsmen wove the Talitot. Traveling salesmen sold their product in all the Jewish communities both near and far. The abundant surrounding forests were the reason that many wealthy lumber merchants lived in the town. Among them was the renowned many-branched Buchman family that controlled the lion’s share of the industry. Many of the townspeople, who for whatever reasons were not involved in Talis manufacturing, were employed as clerks and loyal workers in the lumber trade. Especially noteworthy was the wealthy and philanthropic lumber merchant R. Hanokh Henekh Buchman who merited two tables [professions] and Torah and greatness were concentrated in his very being. In 1875 he transferred all of his extensive possessions, both in cash and in timber, to his sons and he himself, went on aliyah to Eretz Yisrael. All the clerks, his many employees who earned their livings with great dignity from his enterprises, along with thousands of other residents of the town and the surrounding areas came to take leave of him and to witness a rare event—how a Jew departs to go on aliyah to Eretz Yisrael in a horse-drawn wagon (as far as the port of Odessa). Train service was not yet widespread in those days. He settled in Safed, the city of the mystics and occupied himself with the study of Torah and philanthropic activities. He discovered that the Mikveh (ritual bath) of the Holy Ari was in ruins and the wall around the cemetery was broken in many places. To repair them he used all the money he brought with him and afterwards his sons sent him funds from abroad for his upkeep and for charitable deeds. He died in Safed in 1880, after living there for about five years. In the beginning of our century, R. Ya’akov Leib Buchman lived in the town. He was also a very prominent lumber merchant, very devout, generous and his house was always open to strangers. His children who lived in town and in the surrounding area followed in their father’s footsteps and were well known for their many good deeds. That lasted until the Russian Revolution when life changed. Besides Talis manufacturing, printing and the lumber industry for which Sudilkov was famous, the town had several tanneries, a factory for low-priced furs for farmers and some workshops that produced wooden barrels for the sugar factories of Count Potozki in nearby Shepetovka. From those days, the name of the owner of the fur factory, R. Nisan Handler, is engraved in memory. The factory supported many people in town who worked there as clerks and laborers. He was well known in the area for his good heartedness and his unrestrained philanthropy. The day of his death made a sad impression on all the town’s residents. No infant remained in his cradle as everyone joined together to pay their last respects and to speak the praises of the deceased on his final journey. R. Shmuel Handler who was a very learned scholar continued in the production of furs for the farmers. He eventually left the business to become the rabbi of an important community.

In the course of my own research on the Internet I came upon a series of descriptions of many of Ukraine’s Jewish cemeteries, written by local professional researchers and financed by the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. In their catalog of sites I discovered that two cemeteries still exist in the area where Sudilkov was located. One is the sacred Jewish burial ground of the former town and the other is a mass grave where the inhabitants were assassinated in 1941.

Sudilkov cemetery, photo by Miriam Weiner in 2000 The old Jewish cemetery was visited by Peysahov Dmitriy Berovich of Kiev (40-let Oktyabrya str., 48, apt. 6; tel: 044-2650346) on October 31, 1994. In the survey, labeled “US Comm. No. UA22070101”, he claims to have interviewed local non-Jewish residents for his information. He asserts that the “present town” population is 5,001 - 25,000 with under 10 Jews. Clearly, what he hastily describes as the “present town” is only a suburb of nearby Shepetovka, the expanding perimeter of which partially engulfed the area where Sudilkov once lay. His figures obviously conform to rigid numerical categories formulated for the purpose of his survey. Thus, by “under 10 Jews” he seems to mean “no Jews”. (Let us remember that Weiner, who spent several days there, did not succeed in finding any). Berovich’s succinct essay on the cemetery is so precious that I think it is best to cite him word for word, in spite of his grammatical errors. He writes, “The earliest known Jewish community in this town was 16th century. The Jewish population as of the last census in 1939 was 1,842.” He seems to imply here that the town was not a Jewish shtetl but a community which included both Jews and gentiles. However, given the fact that Sudilkov was all but wiped out in World War II, I believe it is likely that its residents were primarily Jewish. Otherwise, a substantial Christian community would have survived the Nazi genocide. He continues, “The Jewish cemetery was established in the 16th century. Photos of the Jewish cemetery in Sudilkov:

The last known Jewish burial was 1948. The type of Jewish community which used this cemetery was Hasidic. No other towns or villages used this cemetery. The cemetery is not listed and/or protected as a landmark or monument. “The cemetery location is urban, located by water, isolated, marked by signs in other languages. It is reached by turning directly off a private road. The access is open to all. The cemetery is surrounded by no wall or fence. There is no gate. There are 21 to 100 stones, most in there original location. Between 50% - 75% of the surviving stones are toppled or broken, whether or not in their original location. Locations of any stones that have been removed is not known. Stones are datable from 19th century to 20th century. The cemetery contains no known mass graves. “The cemetery property is now used for agricultural use (crops or animal grazing). Properties adjacent it is residential. The cemetery is visited rarely by private visitors (Jewish or non-Jewish). The cemetery has been vandalized occasionally in the last 10 years. The work was done by not applicable [?]. Within the limits of the cemetery there are no structures. Vegetation overgrowth is not a problem. Water drainage at the cemetery is a seasonal problem. Very serious threat: existing nearby development and proposed nearby development. Moderate threat: weather erosion, pollution and vegetation. Slight threat: uncontrolled access and vandalism.” As for the mass grave site, it was visited by another professional researcher, Oks Vladimir Moiseevich of Odessa. He gives his address as 270065, Odessa, Varnenskaya str., 17D, apt. 52 [ph: (0482)665950]. His report on Sudilkov, dated March 30-April 18, 1995 and labeled “US Comm. No. UA22070501”, contains some extremely valuable information on the town and its prewar community. Unlike his predecessor Berovich, Moiseevich apparently spent nineteen days in Sudilkov and not just one, perhaps because of the special challenge of gathering information on an unmarked mass grave. He begins his survey by estimating the present population (of Shepetovka?) to be between one and five thousand people, with no Jews—much lower than Berovich’s figure! He then identifies the “village soviet” Kozlov Vladimir Ivanovich and a local official of Shepetovka, Ivan Petrovich (tel: 03840- 51370), as well as some others. These are evidently his research contacts. He also cites two people he interviewed for the survey, Pol’sky B.I. and Berezovskaya L.L., both of Shepetovka. I will come back to his description of the mass grave in the chapter on World War II. Moiseevich declares that “the earliest known Jewish community in this town” existed from the seventeenth century. This is, of course, a century later than Berovich’s date of “16th century”. Unfortunately, neither researcher refers to sources for his dates. Also with regard to the seventeenth century, Moiseevich claims that the years 1648-1649 saw “noteworthy historical events involving or affecting the Jewish community”, but he does not elaborate. Nevertheless, he must have been referring to the great Cossack Uprising discussed above.

|