|

|||

|

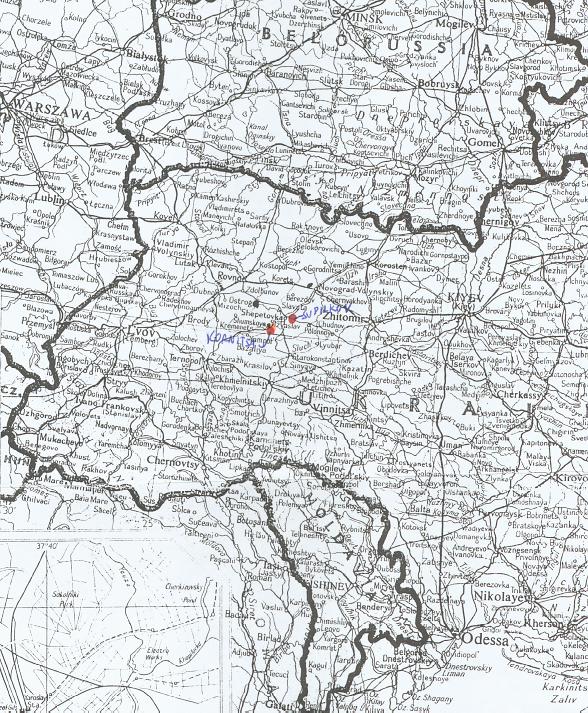

Now that we have some notion of the political and historical events affecting the region in which Sudilkov lay, especially the pogroms and official government policies which precipitated the mass emigration from the Pale in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, we can now turn specifically to the town itself. To summarize, our Grossman ancestors lived in Sudilkov until 1888-1895, when most of them emigrated to the United States of America, never to return to Ukraine. It is anybody’s guess how long our family had resided there—perhaps centuries, perhaps only decades. However, we can be certain that their sudden departure resulted from the officially sanctioned discrimination and violence and against the Jews during the czarist period. The town lay 85km north of the current regional capital, Khmelnitsky (formerly Proskurov), and about 200km east of the major city of Kiev. Shepetovka, located 7 kilometers to the west, is the nearest town which can be found on a map. As I affirmed above, in czarist times Sudilkov was situated in Volhynia Gubernia, in the middle of the Pale of Settlement.

Western Ukraine: location of Sudilkov According to the genealogist Miriam Weiner, an expert on East European Jewry, the town was named Sudilkov “because during Rech pospolitaya there was a court (sudilische).” Thus at some time in the remote past, when the town lay within the confines of the Polish realm, a regional judicial court convened there. Let us begin our inquiry into Sudilkov by drawing upon information which is readily available to us. The climate of the area is continental with relatively mild winters and wet summers. The mean temperature is 43.9° F. In January the average temperature is 22.3° F and in July 64.6° F. Average yearly precipitation is 750 mm, July being the rainiest month and February the driest. Winters must have often been harsh at the time our ancestors lived there, since snow and ice cover the ground for much of the year. At times the roads in and out of town would have been totally impassable. Summers were relatively cool, with many chilly evenings and a good deal of rain. Most of the land in the area was used for farming, and slogging through muddy fields in springtime to plow the earth must have been routine. However, the soil is very poor and currently requires special fertilization with minerals in order to yield a decent harvest. Much of the land is used for grazing animals, and surely many Sudilkovers had cows, horses and mules. The arable spaces around the town are hemmed in by the surrounding pine forests, where one can find an abundance of blueberries, cranberries, currants, damsons and a variety of wildlife. The water supply must never have worrisome because of the abundance of rivers and streams issuing from the Carpathian Mountains to the southwest. The Gouska river, a tributary of the Dnieper, flowed right through town.

Sudilkov boundary marker in March, 2000 Until very recently I was unable to find much information on the history of Sudilkov. In the United States all that was available were four pages from Miriam Weiner’s book, Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova (1997). The breakthrough came in the spring of 2000 when Paul W. Ginsburg of Bethesda, Maryland launched his website entitled “Sudilkov Online Landsmanshaft” (www.sudilkov.com). The site not only includes old maps of the town and surrounding region, but two precious essays on the history of Sudilkov. The first is an anonymous Soviet-era piece entitled “History of Sudilkov”, translated from Ukrainian into English by Viktoriya Khlimenko and kept on file in the Historical Museum of Shepetovka, located at 52 Karl Marx Street, Shepetovka, Khmelnitsky Oblast, Ukraine 30400. The second is an excerpt from a book by Shprintza Rokhel entitled Yalkut Volhynia (Tel Aviv, 1948), from the chapter “An Anthology of Memories and Documents”, edited by A. Avsihai and H. B. Eilon, volume 2, no. 9, Av 5708; the book was translated from Hebrew into English by Shalom Bronstein (Jerusalem, Tishrei 5761/October 2000). Henceforth I will refer to the two essays as Khlimenko and Rokhel. According to Khlimenko, the early inhabitants of the territory where Sudilkov is situated were pagans who were converted to Christianity in the course of the tenth century. From then through the eleventh century a state known as Kievskaja Rus dominated the region through a network of military chiefs. An old Russian tribe occupied the area where Sudilkov would later be founded, and worked the land using iron axes and iron-shod wooden ploughs. In 1240 the Tartar-Mongolian hordes passed through and devasted the inhabitants. The kings of Poland-Lithuania extended their realm to the east and annexed the area in the course of the fourteenth century. An old legend relates that many local serfs were sentenced to life imprisonment in the dungeons of a castle near the village Belokrinich’ye for rebelling against the authorities. Khlimenko claims that the town “was founded between the 16th and 17th centuries on the commercial road from Polonnoye to Zaslav. After the long Polish-Lithuanian occupation Sudilkov belonged to Count Ostrozski. The oldest document referring to Sudilkov is dated 1534 and describes a dispute between the counts K. I. Zaslavski and Ostrozski regarding their claims to the territory. Count Zaslavskij emerged as the victor of the dispute.” This is confirmed by an old Polish encyclopedia entry on Sudilkov which a Pole named Tomy Wisniewski whom I contacted on the Internet was kind enough to Email me (translated by a Polish friend of mine, Edward Skraba, from Polish to Italian, which I then translated into English). Khlimenko continues, “The second document in the Sudilkov archives is a letter written in 1632 to Count Zaslavski from an agent Vishotravka. The agent was sent to observe the numbers of Cossacks passing through his territory. He wrote that he had seen Cossacks in Sudilkov on the Sinjavskij estate, and that they then turned to the Zaslavski estate where they decided to stay and wait for representatives from the central official authorities.”

On February 2, 1724, a law was drawn up in the castle of Sudilkov by the local count allowing weaving mills for the production of linen. In 1717 privileges had also been awarded to smiths as well as ceramic and sewing factories. This was the beginning of industrial development in the town (Khlimenko). In the mid-eighteenth century Sudilkov belonged to Stanislawa Lubomirskiego, who was born in 1738. Khlimenko reports that he lived in Rovno and wielded much power in the region. Among his many titles he was Earl of Visniche, Konepolskij, Rovno, Sudilkov, Shargorode, and Jagorlike. Lubomirskiego later handed over Sudilkov and two other towns, Dubno and Stepan, to Andrea Mikolaiowi Miodzieyowski (1717-1780), bishop of Poznan and Chancellor of the king of Poland (encyclopedia). In a decree of May 11, 1771 the czar permitted the latter to organize a market in Sudilkov (Khlimenko). After the death of Miodzieyowski the territory was inherited by Count Jan Dukan Grocholski (1762-1807), one of the knights of the king and the husband of Ursula Wislocka (encyclopedia). Grocholski did much to improve the economic situation of Sudilkov. Among other things he repaired the castle and roads and demolished old houses and built new ones (Khlimenko). According to the enyclopedia he “built a grandiose palace in Sudilkov in what was apparently the style of Louis XV. Near this palace he also built a little church. Grocholski, who was never loved by his people, resided in the palace until his death. The edifice did not survive for very long, for it burned in a fire in 1859. After the fire the remains of the palace were visited by T. J. Stecki, who found the structure without a roof. The story goes that some paintings of the Grocholski family and some books from the library were saved. After the fire these objects were put into storage where they were forgotten. The new owners never rebuilt the palace, and no trace is left of its former glory.” After Grocholski’s death Sudilkov and the other towns were inherited by his son Rafal. “Born in 1798, probably in Sudilkov, Rafal died without heirs in Florence in 1848 or 1850. In 1831 there was an insurrection which forced him to leave his lands [which were confiscated by the state] and go into exile abroad. All of his property was recovered by the son of the sister of Rafal Grocholski after a legal battle, [after which] the Russian General Bibikow ordered its transfer to the rightful owner”. (encyclopedia) According to Khlimenko, in 1883 Germans settled and engaged in agriculture in Sudilkov in a place that is now called “Kolonia” (colony). In 1905 there were strikes in the factories and farms that were owned by Zacarzevski and Zavadski. As a footnote, I cite an anonymous short essay I found on the Internet which has little to do with anything, except for the fact that Sudilkov is mentioned: Ignacy Jan Paderewski was born on Nov. 18, 1860, in the village of Kurylowka in southwestern Russia, a region that originally was part of Poland. His father, a manager of several large estates, took part in the Polish uprisings of 1863-64. He lost his mother when he was only a few months old. Ignacy was brought up by his father and his father’s sister, who lived in Nowosiolka, near Cudnow. In 1867, his father, Jan Paderewski, married again. The young lady of his choice was Anna Tankowska, with whom he had three children, Jozef, Stanislaw and Maria. Jan Paderewski was arrested for assisting the National Insurrection of 1863, and on his release was forced to leave Kurylowka. He moved to Sudylkow in Volhynia, where he became administrator of the estates belonging to the Szaszkiewicz family. As his son Ignacy displayed an exceptional musical talent from early childhood, he decided to give the boy a musical education. To begin with, he engaged private tutors (W. Runowski, P. Sowinski and M. Babinski) and in 1872, placed Ignacy in Warsaw’s Institute of Music, where the latter learned to play the piano under the watchful eye of such professors of music as Juliusz Janotha, Rudolf Strobel, Jan Sliwinski and Paul Schlozer. From this piece of lore we learn that the Szaszkiewicz family, who were certainly non-Jewish, possessed considerable estates around Sudilkov and had their administrative headquarters in town. Perhaps they were descended from an old feudal family which ruled the area in pre-modern times. In the Khlimenko account of the history of Sudilkov following the Russian Revolution we can sense a strong element of Soviet propaganda. Nevertheless, his text, probably written during the time of Kruschev, is the only source available to me on the town’s twentieth-century history: With great pleasure the inhabitants of Sudilkov received the news: “The Czar has been overthrown!” A revolutionary committee was immediately established. Yakov Alexsandrovich Lobunezh, a former soldier in the Imperial Russian Army, was elected the first chairman. Soon afterwards farmers were punished for exploitation. In the beginning of 1918 Sudilkov was occupied by German soldiers who terrorized the village inhabitants. Potozki’s son, a former officer in the Imperial Russian Army, returned under cover of the German army in Shepetovka. Together with Potozki, a group of Ukrainian Cossacks led by Zolotarenko arrived to retake Sudilkov. Everywhere in the district, including Sudilkov, a decree was promulgated that property of the landowners should be confiscated. Opposition against this decree was punished with the death penalty. Zolotarenko’s soldiers were unmerciful against the farmers and confiscated and divided the landowners’ property among themselves. In the Shepetovka-Sudilkov and Majdan-Villa area a group of gangsters under Sokolovskij harassed the population. To protect the villages against these gangsters, a Red Guard was established, led by Danila Ivanovich Kruzhilo and Jacov Alexandrovich Labunech, inhabitants of Sudilkov. In the fall of 1918, the Red Army liberated Sudilkov and Shepetovka from the Ukrainian nationalists under Simon Petlura. In Sudilkov a hospital for wounded Red Army soldiers was opened. Later a group of Ukrainian nationalists under Petlura recaptured the village and destroyed the hospital. In May 1919, the Red Army liberated the village once again. The civil war continued. The Poles, supported by Ukrainians under Petlura, dressed in French uniforms and, armed with French weapons, won and proclaimed themselves owners of the land. The Galler army left Shepetovka and instead the Pilsudskogo army came. After the Pilsudskogo army the young Count Potochkij´s group took over the occupation of Shepetovka and the surrounding villages. In June, 1920 the village Sudilkov finally was cleaned of its Polish occupants. During the civil war the village had changed occupiers thirteen times. Lenin proclaimed that the land belonged to the people and a new era would be be ushered in. This statement filled the hearts of the peasants with deep satisfaction and hope. After the civil war the village was very poor. 40% of the peasants had no horses and worked for little pay, 50% had horses or bulls and cultivated their own ground, and only 10% were considered wealthy. In the village there was neither electricity nor radio. The school system educated students for only three years. One teacher had 30-35 children, mostly from rich families. 95% of the population had no education at all. There were two churches in the village. Newspapers were received but were read only by the chaplain, the teacher and a civil servant. Over time the peasants realized that Lenin’s words would not bring them out of poverty. They understood that cultivating the ground by means of primitive methods would not bring them rich harvests. The Communist Party spent twenty years reorganizing agriculture in a socialist manner. They started kolkhozes (collective farms) on the land of rich peasants, the so-called “kulaks”, and in this way liquidated them as a class. In Sudilkov the first communist committee was organized by the communists Demjan Petrovich Kononuk, Cyril Stepanovich Burcun, and Moisej Zinovievich Vajsberg. In the winter of 1929-1930, on initiative of the committee, poor peasants were assembled and numerous communist propagandists appealed to them to go work on collective farms. This was accepted by the majority of the peasants. The poor peasants Grigorij Fedosijovich Gordijchuk, Anna Fedorovna Shulak and Musij Dmitrovich Vojtuk were among the first to go to the collective farm. They started the work by building stables for the horses, storehouses for the crops and offices for the farm. Kulaks carried out acts of sabotage against the collective farms. They killed the cattle and burnt down the houses of the collective farmers. They also committed arson on the houses of the farmers Gordijchuk and Okorskij. These farmers had taken active part in the organization of a collective farm. But no threats and no actions against them could stop the farmers. By the spring of 1930, 200 families lived in a collective farm. The first chairman was Demjan Petrovich Kononuk. The members of the management were Makar Petrovich Uzcov, Grigorij Feodosijovich Gordijchuk, Ivan Steoanovich Martinchuk, Grigorij Ivanovich Feshin and Oxsana Nechiporivna Okorsca. Anna Fedorovna Shulak, one of the founding members of the collective farm, strove for the goal of harvesting 500 centers of beets per hectare. There were neither tractors nor modern machines for crops and processing, and there was a shortage of mineral fertilizers. However, with hard work she attained her goal. She succeeded and harvested 540 centers per hectare. For this great achievement she was invited to the 11th Congress of Collective Farmers, held in Moscow in February 1935. The work was very hard during the first years on the collective farm. Due to ineffective equipment, the soil was badly cultivated and therefore gave poor harvests. After the civil war and until 1930 seeders were rare. They had no tractors so horse and plough were the only equipment in use. During 1933 and 1934 machines were introduced. In 1933, people in many areas did not have enough to eat, therefore public feeding in collective farms was organized. In the fall collective farmers received a salary of 3 kilos of grain and 1 ruble per working day. The private enterprises had many problems and began to slaughter their own cattle. The population grew and in 1935 four new collective farms were established called Maxim Gorki, A Sickle and Hammer, Stern (populated by Jews exclusively), and 17th Party Congress. Before World War II the population lived well. Sudilkov now had a ten-year school and radio and electricity were available in the homes. Adult schools were also opened. Newspapers and magazines could also be found in every house. Collective farms began to work with tractors. Manual agricultural methods were still utilized. With support of the Communist party the number of collective farms swelled.

In his section on World War II, known by the Soviets as the “Great Patriotic War”, Khlimenko fails to mention the massacres of Sudilkov’s Jews, which comprised a significant percentage if not the majority of the town’s population. His blatant omission clearly reveals his anti-Semitic bias which, of course, characterized the entire history of the Soviet regime as well as post-Soviet Russia. His emphasis is of course on the patriotic activities of the Russian partisan fighters and the victorious Soviet Army:

On June 22, 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union without a declaration of war. Dark clouds hung over the country. The Soviet Army, inferior in numbers, was forced to withdraw from much of its home territory. After six days of fighting, on June 28, 1941 the German army entered and occupied Sudilkov. The population met the Germans with great animosity. In Sudilkov, the Chief of the Police in Shepetovka, son of the former rich peasant Zhogil, organized the retreat with the assistance of Ivan Danilovich Polonchuk, Ivan Karpovich Dazuk, Ivan Petrovich Kravechcij and Ivan Stepanovich Grin. During the German occupation life was hard for the people of Sudilkov. All the people were ordered to repair the local airport and hangars within five days. They were also ordered to protect the airport with soldiers. For this work Russian prisoners of war were involved. The Germans harassed them, did not give them anything to eat, and executed them for the slightest provocation. The residents of Sudilkov brought them food, helped some to escape, hid them, and contacted the partisans. In 1942 fighting continued in the Shepetovka area between the Germans and partisans, led by the junior high school teacher Ivan Alexevich Muzalov. The first partisans who returned to the area were Stephan Petrovich Artuk, Vladimir Sergevich Necheporuk, and the Nikolaj Semjonovich Gavrrishevski family. At this time a Czech group led by Captain Nalepkou also came to assist the partisans. The Czech group was directed to the Shepetovka area to carry out acts of sabotage. After their arrival to the area, explosions were frequently heard in Sudilkov. Production in the local mill sometimes was interrupted and at several times military trains were stopped. In 1943 the number of partisans began to increase. In Sudilkov people feared reprisals by the Germans. The Germans began to transfer civililians to Germany for forced labor. These events fueled the the partisan movement with increased numbers and many people fled and hid in the woods. The partisans of Sudilkov attached themselves to the partisans of the villages Travlin and Khrolin. One night Ivan Mamchur from Khrolin stole 100 mines from a German ammunition depot. The mines were partly used to mine the railway between Shepetovka and Khrolin. Train service was thus disrupted for a week. Micola Petrovich Chorni from Travin took part in many of these actions. His favorite place for ambushes was a site near Sudilkov. When Zhogil, the Chief of Police, realized that the Germans planned to execute him, he fled Sudilkov and joined the partisans. Later he was executed for treason by the partisans. Ivan Grinnik later became Sudilkov’s new chief of police, however he too was executed for treason. After suffering great casualties on the battlefield and by the partisans, the Germans began to lash out at the general population. During their retreat they killed civilians indiscriminately and burned everything in their way. The Ukrainian policemen committed many crimes as well. Frequently they stole food and clothes from the town’s people. The Soviet Red Army finally liberated the area in 1944. Instead of disbanding, the partisans continued to mine railways and burn German depot and command centers. They also killed Ukrainians who collaborated with the Germans. On February 10, 1944, the Kantemeriov’s Soviet Fourth Guard of the tank corps liberated the area. The first unit to enter Sudilkov was the 13th Guard’s Tank Brigade led by Boris Koshechcin. In the final part of his essay Khlimenko treats the period following World War II, with expected emphasis on the communist work ethic. He fails to point out that Sudilkov was all but razed to the ground by the Germans and that the “reconstruction” effort actually involved refounding the town from nothing. When the German occupiers retreated under heavy bombardment, they looted Sudilkov and destroyed everything they could not take with them. All sorts of machines, tractors, and agricultural equipment was stolen by the Germans. At the end of the war the peasants began to restore the collective farms Maxim Gorki, 18th Party Congress, and Victory. The peasants worked hard and ploughed the fields with cows as draft animals, dug with spades and carried fertilizer in bags. The soil was badly cultivated and gave poor harvests. It took the collective farms many years to recover from the destruction caused by the German occupation. In 1950 the collective farms of the villages Sudilkov, Luzichno, Bilocrinicha and Rudni-Novenko began to work together. Together they had 7,311 hectares of land with 1,229 houses. Productivity increased considerably. The number of working days for cultivating one hectare of soil decreased accordingly. In 1956 cultivating one hectare of soil required 4.6 working days. In1957 it required only 2.8 days. After the war, harvesting one hectare of corn required 15 working days. By the mid-1950’s it was shortened to only 3 days. All work was totally mechanized. The central management of the collective farm Maxim Gorky was situated in Sudilkov. The profit from the collective farms rose year by year. The peasants of the collective farms receive medical treatment by two doctors together with some qualified medical assistants. There is a village shop, two grocery shops, stationer shop, cafes, movie house, library, sewing workshop, and hairdressers. There are 1,485 houses in Sudilkov. The population is 5,305. Near the village of Volin-Podilska there are quarries of hard crystal granite. In areas where there were dense forests in 1905 valuable granite stones are now extracted. Granite stones from Sudilkov are exported for use all over the country. The granite is then used for decorative and construction purposes. The majority of people in the area work in the factories of Shepetovka and Sudilkov. Others work in agriculture growing grain, white beets and vegetables. There are also large orchards in the area. Milk and meat is produced in the kolkhozes (collective farms). |