|

|||

|

Trapped between Central Europe and Russia, unwanted by neighboring countries, deprived of their rights and subjected to countless depredations, the Jews fared poorly in the Pale. Many eked a living at subsistence level, worrying about whether the next crop would yield enough to avert hunger for another season. Although a certain number among them managed to accumulate some wealth, czarist policy prevented the vast majority of them from improving their lot. Deplored and rejected by gentile society, Jews naturally insulated themselves within their communities and around their synagogues, always in fear of the czar’s next decree. They especially dreaded forced military conscription, which often saw thousands of young men carried off to distant wars with little or no warning.

Russian pogroms 1871-1906 The worst times came in the last decades of the czarist regime, as pogroms became more frequent and devastating. Derived from the Russian word meaning “to wreak havoc”, a pogrom is an organized attack, often a massacre, against a minority group, particularly Jews. In the Russian Empire the Jews had been subject to such persecutions for centuries, often at the instigation of local government officials. However, in the period between 1881 and the Russian Revolution they were especially violent. A typical pogrom lasted from one to several days. With astonishing brutality, peasants and even city folk would riot against their Jewish neighbors with little fear of punishment, looting and burning their synagogues and businesses. When the police finally intervened little or no effort was made to apprehend the attackers and bring them to justice. The anti-Semitism which led to the Russian pogroms of 1881-1917 was in part catalyzed by events in the years immediately preceding them. The freeing of the serfs in 1861 meant that uneducated peasants flooded the cities looking for work. There they often ran into conflict with the better-educated and wealthier Jews, against whom they began to organize and riot. According to Wheatcroft, anti-Jewish sentiment had been on the rise since 1863, when many Jews supported the Poles in the Polish Rebellion. Things worsened in 1867-1870 when a Jewish convert named Jacob Brafman published “The Book of the Kahal”. Allegedly based on a book of minutes written in 1795-1803 by the Minsk community of Jews, it supposedly revealed a dishonest, anti-Russian attitude on the part of the Jews. The book was widely available and did much to fuel anti-Semitism. In addition, many admired writers and intellectuals, such as Dostoevsky, were notorious Jew-haters. Much of the hate was driven by envy of recent Jewish economic advances, as Jewish traders and merchants, in spite of their legal disadvantages, began to compete in earnest against older gentile businesses. Frequently, such jealousy and malice erupted into violence. In 1871, the Greeks residing in Odessa, stirred up by local Russian officials, rioted against the Jews. Such attacks became increasingly common as Jews were increasingly seen as both anti-Russian and anti-Christian. Often the old blood libel accusation was all that was necessary to trigger a massacre. Rising anti-Jewish sentiment in Western Europe probably had some influence on the discriminatory policies of the czarist regime. Indeed, in the late-nineteenth century the entire continent seemed to be engulfed in a wave of hatred for the Jews. In Germany and elsewhere in this period a new anti-Jewish doctrine called anti-Semitism sprang into being. Although anti-Jewish feeling had run high in Germany for centuries, the new anti-Semitism differed from past anti-Jewish belief systems in its claim to be “scientific”. Embracing the concept that “all people are governed by racial law”, it identified Jews as a racial group inferior in certain ways to the rest of the human species. As a result it came to be considered defiling and corruptive for Christians to mix with Jews, either socially or by marriage. By 1879 a German Anti-Semitic League was formed which called for discriminatory laws against the Jews. Thus, much of the ideological basis for Hitler’s crimes existed long before he was named chancellor of Germany in 1933. In 1894 in France the state intelligence service discovered that a spy had infiltrated military headquarters. Since the authorities, humiliated, had no idea who the spy was, they decided to accuse the only Jew at hand, Captain Alfred Dreyfus. In a rigged trial the French military found Dreyfus guilty of treason and sentenced him to a lengthy prison term on Devil’s Island. Although he was eventually exonerated and released, long-term damage had been done to relations between Jews and Christians in France. Developments such as these had a significant effect on Russian opinion, especially since Russia, itself a backward, semi-feudal nation of nobles and serfs, looked to the West for cultural guidance. In an anonymously written but well-researched essay entitled, “The Pogroms Against the Jews” (located on the website of the SunStrike Bookstore), it is claimed that the main campaign of Russian pogroms was initiated by Czar Alexander III in 1881. Overcome with anger at the murder of his father Alexander II at the hands of revolutionaries, the young czar immediately blamed the Jews. Although only one Jew, Hesia Helfman, was involved in the attack (Actually, she did not participate directly, but only sheltered some of the conspirators) the story was circulated that the Jews had been behind it. Wheatcroft claims that Alexander III was aware that the Jews were innocent of the conspiracy, but nevertheless spoke out severely against them. He appointed a reactionary anti-Semite, Nikolai Ignatiev, as the new Minister of the Interior and organized two years of riots aimed at the expulsion of the Jews from his realm. A series of Reuters telegrams sent in April and May, 1881 and published by The Jewish Chronicle on May 6, 1881 tells of the anti-Jewish disturbances in the town of Elizabethgrad. The first was communicated from St. Petersburg on April 20: “Serious disturbances having their origin in the superstition of the peasantry regarding the Jewish Passover rites have occurred at Elizabethgrad in the province of Khersan. The popular excitement against the Jews led to an attack upon the synagogue which was destroyed by the mob. The aid of the military was called in to repress the disturbance, and a large number of the rioters were killed by the troops.” A second telegram of a few days later reports: “An official account of the anti-Jewish riot at Elizabethgrad on the 27th ult. states that some houses inhabited by Jews and several public houses belonging to members of that faith were attacked and pillaged by the populace. The disturbances continued until the morning of the 29th ult., when order was reestablished. One Jew was killed and several other persons were seriously injured by the rioters. The authorities have instituted a strict investigation into the circumstances.” Of course, such official accounts must be read with a critical eye, since they were often drafted or influenced by the authorities. Even if the government did not participate directly in the pogrom, which is unlikely, it is doubtful that anything was done to prosecute the rioters. Another Reuters telegram from St. Petersburg, dated May 3, 1881, relates: “The following details have been telegraphed by the Odessa correspondent of the Times: Since my telegram to you of yesterday stating that anti-Jewish riots had broken out at Elizabethgrad, a town of about 40,000 inhabitants, situated in the government of Kherson, the following particulars have been published here upon the authority of Prince Dondonkoff Kornakoff, the provincial governor general of Odessa. The disturbance commenced at 4 PM last Wednesday, and the contents of several Jews shops were stolen, damaged or destroyed. The police called in the aid of the troops, who made every effort to stop the pillaging. This was, however, only effected on the following evening, and with great difficulty on account of the number of peasants who had flocked into the town from the surrounding villages to participate in the general plunder. During the night of the 28th inet. there arrived at Elizabethgrad three squadrons of Uhlans and yesterday a battalion of infantry. One Jew was killed, but the number of wounded is not great.” In a later telegram the correspondent states that “at Elizabethgrad things have remained quiet ever since the anti-Jewish riots. These were quelled last Thursday evening. It appears that 400 persons were arrested. The rioting arose out of a dispute between some Christians and Jews. The quarrel led to a general fight, which, according to the Elizabethgrad Vestnik, assumed a more serious nature upon revolver shots being fired from some Jewish houses. The Christians then attacked the houses and shops of the Jews indiscriminately by smashing doors, breaking windows, &c., up until a late hour on Wednesday night. The violence was continued throughout Thursday, but in a different form. The Jews, finding themselves vanquished, offered no further resistance and all fighting ceased; but the rioters, aided by an influx of peasants from the surrounding villages to join in the general melee, sacked the houses of the Jews, destroyed their furniture, and stole or spoiled there wares. The military and police are represented as having done what they could to establish order, but failed to do so at once, because while they were attempting that in one place, disorder was breaking out in another. The Jewish population of Elizabethgrad is reckoned at about 10,000 persons and more than half their houses are completely ruined.” We know now that even the state police participated in disturbances like those at Elizabethgrad. Plundering and murder were openly encouraged by the authorities, while official accounts were censured before publication. The Russian Orthodox Church meanwhile did nothing to stop the carnage, but instead spewed anti-Semitic rhetoric, blaming the Jews for the misery of the peasants. After an investigation of Alexander II’s assassination, the May Laws of 1882 were drawn up, enforcing Christian holidays and further restricting Jewish residence. In response to these measures a more liberal sector of the government formed the Pahlen Commission, which was to report on the general legal status of the Jews. It was soon dismissed as being too sympathetic to the Jewish cause. Instead, the May Laws were strengthened with amendments curbing the admission of Jews to secondary schools and universities.

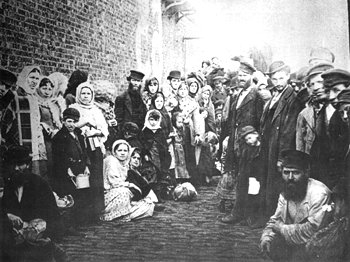

Jewish refugees at port of Liverpool, 1882 The suffering of the Jews in Russia entered a new phase with the mass expulsions from Moscow and St. Petersburg in 1891. From that moment on attacks on the Jewish population intensified and deportations occurred more frequently. With the Kishenev pogrom of April 6-7, 1903 the cruelty of the anti-Jewish conspirators reached a new high, as attacks included more killing, and not just burning and looting. In a city that had 50,000 Jews and 60,000 Christians at least 45 Jews were murdered and 86 seriously wounded in a single attack, while over 1,500 homes were pillaged. The evidence strongly suggests that the Russian government had a hand in the planning (Wheatcroft). The brutality of this pogrom fueled a growing desire among Jews to leave Russia. In the next year the Union of the Russian People, an extreme nationalist political group, was founded. Among other activities it distributed anti-Semitic propaganda and financed paramilitary squads which further harassed the Jews. Czar Nicholas II accepted honorary membership in the group and gave it and others like it official protection. In the final years of the czarist regime the Jewish security situation deteriorated even further. On 19-25 October and 1-7 November, 1905 a total of 660 Jewish communities were attacked. In Odessa alone 300 Jews were killed and thousands wounded, while 40,000 were ruined financially. In total approximately 1,000 were killed and 7 to 8,000 wounded, with about 63 million rubles worth of property damage (Wheatcroft). At that point the Jews began to organize armed self-defense units in order to repel the aggressors. The Russian army was sometimes called in to fight against these newly formed militias. Unfortunately, the Jewish units were unable to prevent the Kiev pogrom of 1907, which was at least as devastating as the one in Odessa. As the Bolshevik menace grew, Czar Nicolas II took increasingly extreme measures against the Jews, whom he began to see as a direct threat to his authority. One of them, Leon Trotsky, was among the revolutionaries’ most revered intellectuals. In their belief that the end of the czarist regime could only improve their lot, many Jews rushed to fill the ranks of the political opposition. In the years leading up to 1917 a huge number of Jews were deported from Russia. Many of those who remained nearly died of starvation. Meanwhile, the government actively supported the publishing of anti-Semitic literature and propaganda. In the period 1905-1916, 14.3 million copies of 2,837 anti-Semitic books and pamphlets were sold. Nicholas II is reputed to have donated 12.2 million rubles of his own funds to the smear campaign.

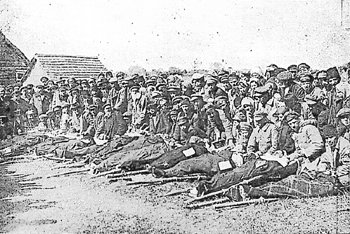

Victims of a pogrom in Ukraine, 1919 In 1917, with the murder of the royal family and the violent overthrow of the czarist regime, all repressive edicts regarding the Jews were repealed and the Pale of Settlement was abolished. However, the new communist ideology of tolerance was very short-lived, and as early as 1918 the Jews were victims of several vicious attacks. Massive pogroms continued in the Ukraine until 1921. According to David A. Chapin, who posted an account of his travels through Ukraine on the Internet, Proskurov (later Khmelnitsky), one of the cities nearest to Sudilkov, “was the site of the worst atrocity committed against Jews this century before the Nazis. In 1919, during the Ukrainian civil war, Peliura and his band of Ukrainian nationalists massacred a large percentage of the Jews who lived in the town. More than 10,000 Jews were killed. We tend to forget that these pogroms were so horrible, since they fall in the shadow of even worse atrocities committed by the Nazis.” This attack must have been terrible for the residents of Sudilkov, many of whom suffered the loss of friends and relatives who had gone to live there. For more information on the Russian pogroms against the Jews in the nineteenth century, I strongly recommend I. Michael Aronson’s book, Troubled Waters: The Origins of the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. |