|

|||

|

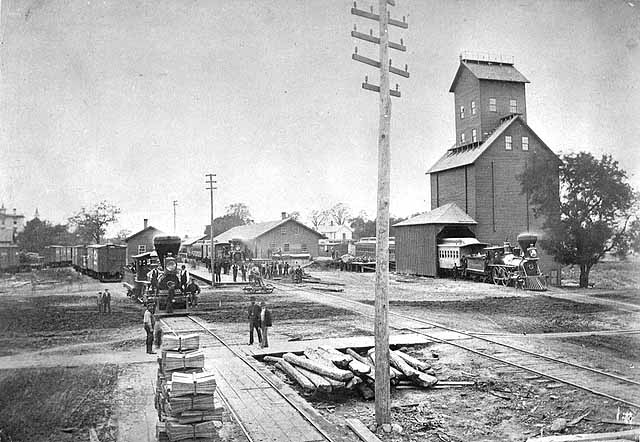

To summarize, the first wave of Jewish immigrants to arrive in Minneapolis settled in the area around Washington Avenue North and lived alongside non-Jewish immigrants, mostly from Western and Central Europe. In the course of the previous two decades the quarter had been transformed from an area of sawmills and railroad depots into the center of a booming metropolis.

St. Paul and Pacific Railroad Depot, Washington Avenue North and 4th Avenue North, photo 1874

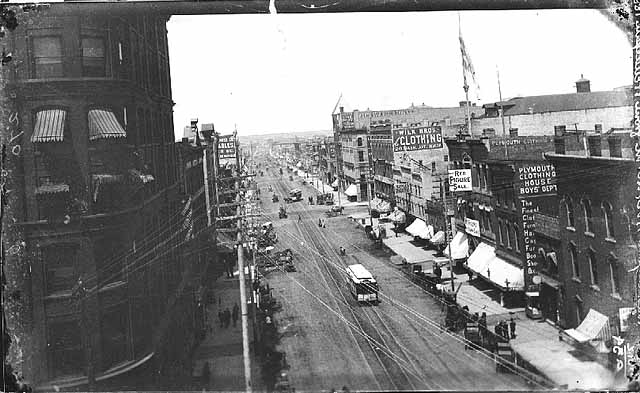

North Minneapolis business district, from 2nd Avenue North and 3rd Street, photo circa 1895 For the Jews the northern third of downtown had become a kind of halfway house for adjusting to the new society around them, a transitional space between their European past and the New World. Within the boundaries of their neighborhood they instinctively sought to recreate the ambience of the shtetl—its intimate scale, unity and inner warmth. They lived within a short walk of one another. They depended upon each other for moral and financial support. They greeted each other in Yiddish in the streets, prayed together, and shared news of the latest developments in Europe. In time they opened kosher food stores and other small businesses, the same kinds of family-run operations that had been familiar to them in the Old World. Oftentimes they began their careers in America where they had left off when they fled Europe—as bakers, furriers or shoemakers. Washington Avenue North was the biggest and busiest thoroughfare and became the main north-south drag through the area where the Jews were concentrated.

Washington Avenue North from Hennepin Avenue, photo 1885

Minneapolis in 1900, Washington and 3rd Street Many of the first Jewish businesses sprang up along that street, as the smell of schmaltz, kreplach and kishke wafted around the side-roads and alleyways. By the mid 1890’s there were hundreds of Jews residing in the neighborhood, many of them dressed in the same peasant garb and hats they had worn before immigrating, and they kept on coming. Eventually the Minneapolis Jewish population reached a critical mass, and the first religious congregations were established. I found a 1909 photograph on the Minnesota Historical Society website of a typical Jewish tenement in the neighborhood.

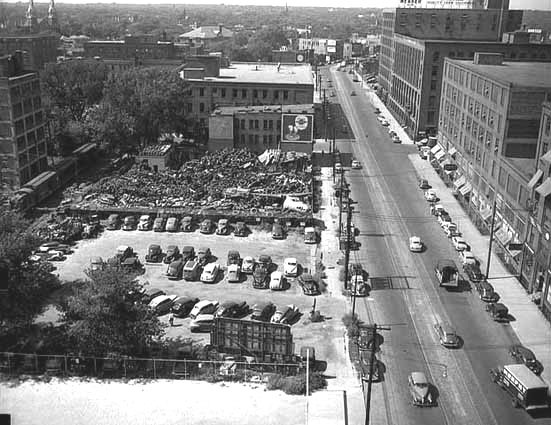

Jewish tenement, 6th Avenue North and 3rd Street, 1909 In 1997 a Minneapolis scholar and author named Abraham Heschel posted an essay on the Internet entitled “The Jews are G-d’s Stake in Human History”. In it he summarizes the history of the earliest synagogues and Hebrew schools in Minneapolis. He writes, “In 1894 Jews from the Ukraine and Bessarabia established a house of worship in a small upstairs room at Seventh and Washington Avenue North, while ‘Litvaks’ from Western Russia established a house of worship in a loft at Second Street and Sixth Avenue North.” The building which housed the former was demolished by 1949 and replaced by a parking lot, which can be seen in a photogrpah of that year; the Johnson Nut Factory, erected sometime after 1910, is visible across the street.

Our Berman and Grossman ancestors must have attended one of these two proto-synagogues, both of which were located very near their homes. If I had to guess I would say they went to the latter, since it lay squarely between 517 and 609 North 2nd Street and directly across the street from the Soo Line Freight Depot.

Soo Line Freight Depot, 500 2nd Street North, circa 1905 This was the first synagogue that immigrant Jews encountered when they exited the station, just down the street, and it must have been a very welcome sight. After its consecration in 1894 there must have been a constant crowd of men gathered in front of the building, schmoozing or arguing about some point in the Talmud, especially in the summer months. New Jewish arrivals from the train station were probably greeted warmly by their brethren and bombarded with questions before they could get across North 2nd Street! It is not hard to imagine that Moishe and other Grossmans or Bermans spent long hours in front of the new center of worship, watching the immigrants amble down the street, wondering which train would bring them more of their loved ones. I found a 1949 photograph of 2nd Street North, looking south from the corner of 5th Avenue North; although the buildings on the right are on the 500-block of 2nd Street North, they give some idea of the general aspect of the buildings on the 600-block, which included the synagogue as well as no. 609.

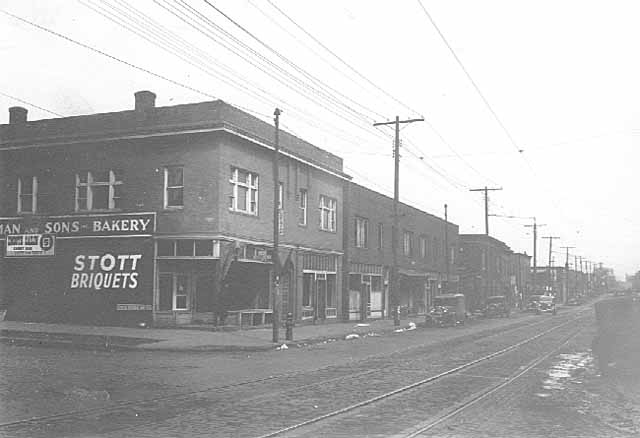

2nd Street North, looking south from 5th Avenue North, 1949 Heschel continues, “Like most immigrant parents [the Jews] realized that ‘learning’ was the measure of success. They formed the Hebrew Free School in a room made vacant when a butcher moved his shop. The address was 613 North 5th Street, the language was Yiddish and there were about twelve students.” It was situated just across the street from the building which would house Morris Meats, Moishe Grossman’s first butcher shop, between 1910 to 1912. The founding of this school must have been a very important event for the Bermans and Grossmans, among whom was a growing number of children who needed to be educated in the Jewish faith. I would imagine that there was at least one Berman or Grossman among those first twelve students, but I will have to do more research in order to be certain. Heschel proceeds, “In the latter part of 1894, the new building of Kenesseth Israel, [one of the first North Side Synagogues], was dedicated. The Hebrew Free School, which at the time was short of funds, was housed in the vestry room of the Kenesseth Israel Synagogue and the Kenesseth Israel Hebrew Free School, precursor of the Minneapolis Talmud Torah, was formally launched. It was an old-type school with teachers of the ‘melamdim’ type and a ‘heder’ atmosphere.” The synagogue and Hebrew School were located at Lyndale and 5th Avenue North, an area which was destined to become the principal Jewish neighborhood in Minneapolis.

Kenesseth Israel Synagogue, 519 4th Street North, 1934 It is almost certain that Jacob Grossman, Moishe’s uncle and a scholar of Hebrew texts, taught at that school the year it opened. He lived only three blocks away, at 801 N. Lyndale Avenue., and in the 1893 Minneapolis directory his occupation is given as “teacher”. Heschel continues, “In 1901, Rabbi Solomon Mordechai Silber became rabbi at Kenesseth Israel and exerted all his influence in promoting the interest of the school. He assumed the religious leadership of Kenesseth Israel and served the entire Orthodox community for nearly twenty-five years.” Rabbi Silber was a towering figure in the nascent Jewish community and must have been well-known by the Bermans and Grossmans, even if they did not necessarily attend Kenesseth Israel. Heschel’s account of the development of Jewish education in Minneapolis is worth citing. He writes: Another young man with an active interest in Jewish culture was Dr. George J. Gordon. As a 20-year-old immigrant student, Gordon was teaching Hebrew while attending high school and was concerned with what to teach the children. He stated, “I felt as I looked around the North Side community that the heder system here, with its very poor teachers and classrooms and [courses without grades], was certainly not the kind of school that ought to be developed in an American Jewish community. I couldn’t see how much knowledge could be acquired under those circumstances. I was sure that the children wouldn’t even get very much Jewish history. I had talked to a good number of people about the situation and they agreed with me that something ought to be done.” In 1910, Nathan Waisbren, an excellent Talmudic scholar, arranged a compromise which involved severing connections with the Kenesseth Israel Synagogue and establishing an independent Hebrew school. It was moved to a new site at 808 Bassett Place North with Mr. Waisbren as its first president. The Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Talmud Torah was formed in 1911, not just to raise funds, but to bring American Jewish women closer to Judaism and to arouse civic pride as well as Jewish consciousness. This important group of committed women was responsible for the Kosher Dinner Dance, the Purim Food Sale and the Fall Rummage Sale. In February 1911, 32-year old Elijah Avin came to Minneapolis on a fifteen-day trial as a Hebrew teacher. After capturing the hearts of the board he was hired for three years at $100 per month. Mr. Avin introduced a co-ed policy and a hope for a system in which the old that was Jewish would be integrated with the new that was American. At this time the ‘Ivrit B’Ivrit’ method of teaching was adopted and Hebrew conversation was used in the classrooms. From the earliest days, Talmud Torah was blessed with outstanding teachers. Solomon Zemach served as teacher and principal to the elementary department for forty years. Menachem Heilicher, a Vienna-born immigrant, developed the patterns of scholarship and love of Torah, prophecy and Hebrew which inspired two generations of students. Added to the four rooms at Bassett Place were two rooms and a large auditorium. The larger space served as a meeting place for children and acted as a community center which provided a large source of revenue to the school… In 1913, the official name of the school was changed to the Talmud Torah of Minneapolis and by April 1914, enrollment had grown to 275 children. The Talmud Torah building was at 8th and Fremont. On April 17, 1915, formal ceremonies celebrating a new $45,000 building on the corner of Fremont Avenue North and Eighth Street were held.

Minneapolis Talmud Torah, 725 Fremont Avenue North, circa 1950

At the same time the first class of students, seventeen boys and three girls, was graduated. Shortly after this first graduation, Mr. Waisbren went to see Thomas Lowry, president of the street car company, and Talmud Torah received chartered street cars on Fremont and 6th Avenue North to transport students! The new school had eight large classrooms, one small classroom, one teacher’s room, an auditorium, playroom and library. In addition to regular Hebrew classes, there was a Hebrew kindergarten and a Normal School for the training of Sunday School teachers. Dr. Gordon was committed to making the Talmud Torah the important social service center for the North Side Jews and to establishing a modern Hebrew educational system in Minneapolis. His primary goal was to develop in his community children who could speak Hebrew and thus share in the rebirth of the Hebrew language. Over the entrance to this new building was the inscription: “You shall teach them diligently to your children and shall speak of them.” No longer would children be taught by the Yiddish ‘teich’ method, brought over from the European heder. Hebrew would be the language of instruction and communication in the classroom. The introduction to spoken Hebrew came on the first day of class in the first grade. The eight-year-olds were welcomed by the teacher who introduced himself. “My name is Mar Kass (not Mister Kass). From now on we will only speak Hebrew in this class…” Classes were

held every day Sunday through Thursday. Saturday

morning services were also held at the Talmud Torah.

The South Side branch of the school was opened at Adath Jeshurun

Synagogue in 1920… By the mid

1920’s, the Minneapolis Talmud Torah became recognized as one of the foremost

institutions of its kind in America and was considered among the most modern

Jewish schools in the country. Important

Jewish holiday celebrations and special assemblies of the children took place

during the year. On Purim an

exchange of gifts among the pupils was arranged, and on Rosh Hashanah greetings

were sent among all of them. During

Succoth, a beautiful Succah was built, and on Simhat Torah, the children

themselves participated in the very impressive ceremonies which were enjoyed by

capacity audiences. Festival

programs consisting of plays, sketches, songs and dances were held on holidays.

In 1926, commemorative gatherings were held for Dr. Max Nordau, Dr.

Theodore Herzl and the opening of the Hebrew University in Palestine.

Participation in drives, celebrations and extra-curricular activities

during these years kept the Talmud Torah students in touch with the state of

Jewish affairs throughout the world. B’nai

Hasefer, an assembly of eighteen high school graduates, met to promote the

reading and speaking of Hebrew. B’nos

Zion, a membership of twelve girls, organized to develop a knowledge of Hebrew

and to keep in touch with the progress of Jewish life, while the Barkai Club was

interested in Hebrew drama. In 1926, Dr. Gordon gave up the practice of medicine to

become the director of the Talmud Torah…

To ensure that no child was prevented from receiving a Jewish education,

tuition fee incomes were instituted. It took a decade or two for the Jews living in the area around Washington Avenue North to fully absorb the fact that there was no longer any imminent danger. The days of fear and dread were over and the pogroms were a phenomenon of the past. Suddenly, there were more choices in life than they had ever been accustomed to. It was no longer necessary that they live in a tightly knit community for protection and defense. The former “us and them” mentality gradually faded away, especially as Jewish children began to attend the same elementary schools as their non-Jewish neighbors. Although anti-Semitism was certainly present in Minneapolis in the late-nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth centuries, it never assumed the threatening character that it had in Europe. Jews felt free to venture out of the crowded quarter where they had been living into newer, ethnically diverse neighborhoods. Guita Gordon, who wrote an article in 1986 for the American Jewish World entitled “Minneapolis’ North Side”, claims that “by the first decade of the 20th century the main hub of the Jewish community had moved from Washington Avenue North to Lyndale and 6th Avenue North.

Jewish business off 6th and Lyndale in 1908 That avenue later became Olson Highway, named in memory of Minnesota governor Floyd Olson, who had grown up in that area, and had served as the shabbas goy for many of the people who lived there.” Thus the Jewish population of the city gradually shifted to the west. The construction of Kenesseth Israel Synagogue on Lyndale and 5th Avenue in 1894 was the harbinger of the demographic change. 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Avenues became the main arteries of Jewish settlement from the late 1890’s until the 1920’s. The accelerating influx of Jewish immigrants fueled the expansion westward as the run-down and overcrowded area around Washington Avenue North could no longer accommodate the arrivals. The swanky avenues and newer buildings west of the heart of downtown offered an attractive alternative to the rotting tenements of the previous neighborhood. As we shall see, many of the Grossmans and Bermans, cashing in on their successes in the ten or twenty years since immigrating, joined the general movement to the northwestern part of downtown. The new neighborhood came to be known as North Minneapolis. Gordon provides an interesting, fanciful description of the neighborhood in her article. According to her, Hoag Avenue divided the Irish from the Jewish areas and at one time was a difficult frontier to cross. In those days the city was still characterized by European ethnic neighborhoods. The Sumner Branch of the public library on Emerson and 6th Avenue North was an important place of social gathering for first-generation Americans. I found a 1936 photograph of the intersection, which unfortunately does not include the library since the view is to the west down Sixth Avenue North.

Emerson and 6th Avenue North, looking west, 1936 It was also the meeting place for Boy Scout Troop no. 66, which had many Jews among its members. Immigrant children attended the grade schools Graham, Sumner, Lincoln (later John Hay) and others. Meanwhile, many parents of the children went to night school in order to learn to read and write English. Gordon explains that “North High School was the center of the educational system on the North Side.

Old North High School before 1913 fire, 17th and Fremont Avenue North, circa 1902

North High School, 1701 Fremont Avenue North, circa 1915 It was a school that served as the center of the developing educational wishes of the Jewish community. North High had the reputation as a school that sent a [high] percentage of its students to college. It was an institution that beckoned to each of the children of immigrant parents and to those who had been born [in America] to achieve at the highest levels.” There were some problems with discrimination, however. “For example, the High Y and the Silver Triangles were groups in the high school restricted to Christians. They were service groups and attempted to serve their schools at the highest level of volunteer participation. But Jewish youngsters were not part of that group and they too felt the need to serve their community. And so in about 1922, at North High School, a young men’s group called Menorah and a young women’s group called Kadima were established to serve the Jewish students as service clubs to the high school.” Many of the children and grandchildren of the first Bermans and Grossmans to settle in Minneapolis eventually attended North High, including my own grandfather Norman Bud Grossman (born 5 Apr 1921 in Minneapolis), Moishe’s grandson, who graduated in the class of 1938.

First Mikro Kodesh Synagogue, photo 1910 In addition, I found a photograph of the building at the Minnesota Historical Society in Saint Paul The edifice, the precise address of which was 720 Oak Lake Avenue, occupied exactly one-ninth of the city block. It was a large wooden rectangular structure with a pitched roof. Its architecture was inspired by ancient Etruscan and Roman models such as the temple of Fortuna Virilis in the Forum Boarium of Rome. It had a spacious elevated porch with eight fluted Ionic columns and semi-columns, a simple entablature, and a large triangular pediment pierced by a round window decorated with the star of David. The edifice was five bays long with tall windows and pilasters and had a single front entrance. In the early days of Mikro Kodesh there was no rabbi and there were very few congregants. However, by 1927 there were 250 families attending, including the Grossmans and Bermans, most of whom by then lived in North Minneapolis. Grace, Moishe Grossman’s daughter, and Harry Stillman celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary at Mikro Kodesh. Moishe’s sister Chaya Fraida Berman also attended. In 1927 the building was abandoned and the congregation moved to the newly-constructed synagogue at 1004 North Oliver Avenue, at the intersection of 10th Avenue North. The Oak Lake structure remained vacant until its demolition in about 1935. The new synagogue, a three-story brick edifice with a monumental twin-towered facade, was far larger than its predecessor, with an impressive triple entrance and stone staircase. Unlike the old building, its architecture was inspired more by East European prototypes than by ancient pagan temples. It had the same three-bay facade and tall round-headed windows that were to be found on synagogues throughout Eastern Europe, including the one in Sudilkov. The semicircular element above the facade was reminiscent of countless synagogue facades from Poland to Russia. Awend claims that by 1936 the congregation had grown to about 400 families, reaching a peak of 500 families in 1960. By that time it was led by Rabbi Liebhaber and Cantor Markovitz. The latter, according to Awend, “had impressive credentials as a cantor. He was born in Europe and suffered through the Holocaust, finally being liberated from Auschwitz. After the war he worked for the Irgun in Italy and communicated with Menachem Begin [prime minister of Israel] on many occasions. Always interested in music, even as a young choir boy in Hungary, Markovitz studied music and voice at the La Scala Conservatory in Milan, as well as cantorial schools in Israel. In 1964 he came to Mikro Kodesh as its cantor.”

Second Mikro Kodesh Synagogue, photo 1937

Second Mikro Kodesh Synagogue, photo 1948 Almost as old as Mikro Kodesh was the B’nai Abraham Congregation, a Romanian shul founded in 1891 in the small Romanian Jewish community which had sprung up on the South Side. Located at 15th Avenue South between South 3rd and 4th Streets, its services were always packed with worshippers. Awend asserts that the synagogue flourished especially under the leadership of Nachum Cohen, Charles Juster and Moshe Brille. Only five blocks south of the edifice lived Max Lorberbaum, my great-grandfather and the man I’m named after. His address was 1513 East 18th Street and he lived there during, and possibly before, World War I.

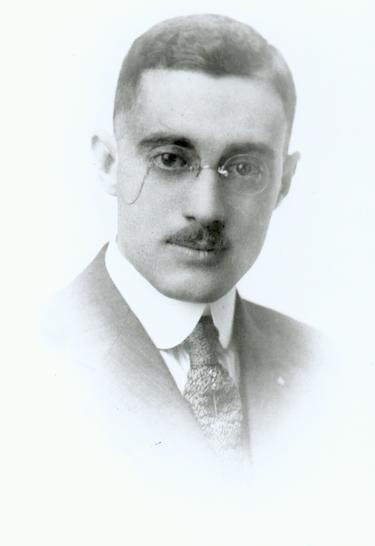

Max Lorberbaum, circa 1920

USS Martha Washington, built in Austria in 1908 and seized by US Navy in 1917 He was accompanied by his father Harsh (Herscu, Harry) Lorberbaum (1845-1928), his mother Havid (1855-1924), and probably by his older sisters Nettie (1882-1963) and Hannah (1885-1951). Harsh Lorberbaum’s grave

Havid Lorberbaum’s grave

Mollie, Nettie and Hannah Lorberbaum, circa 1955 His older brother Samuel (1886-1958) had arrived in Minneapolis two years earlier, in 1907. On his Declaration of Intention to become a U.S. citizen, filled out by his his own hand on October 28, 1918, Max identified himself as “Marko Lorbeerbaum”.

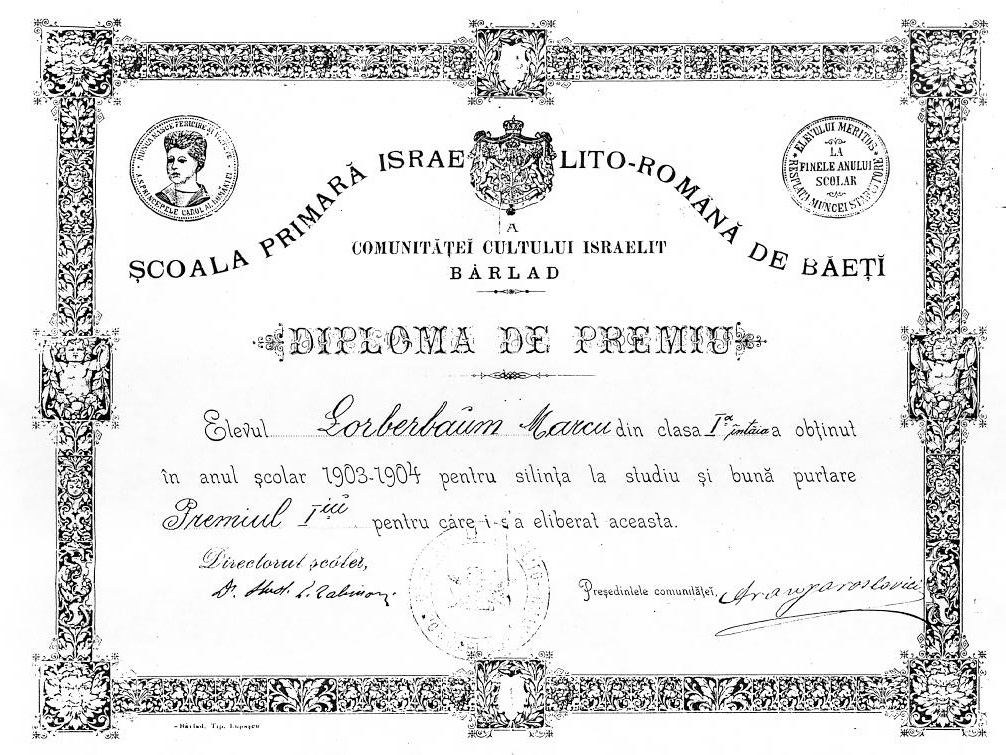

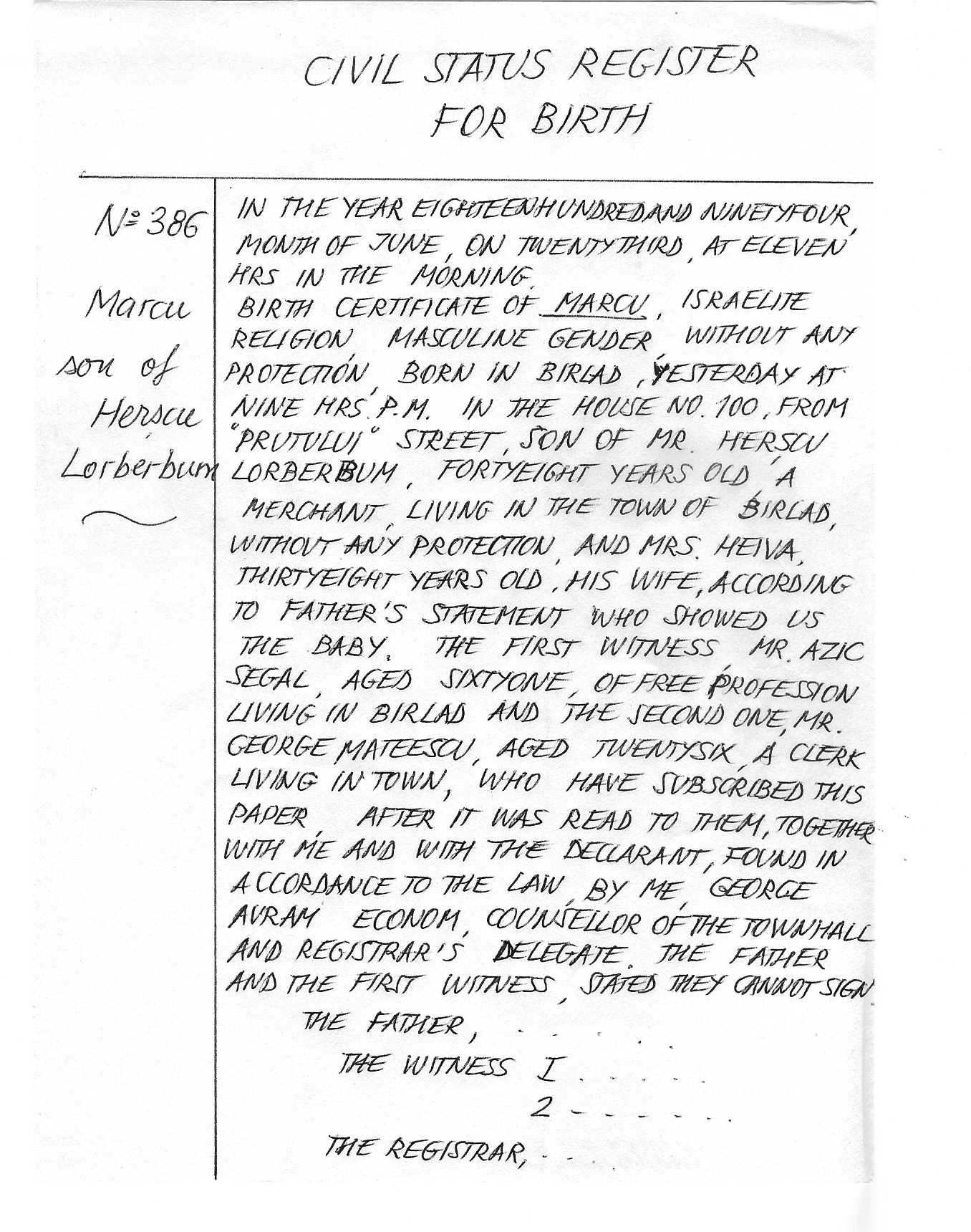

Max Lorberbaum’s birth certificate translated from Romanian He gave his birth date as June 22, although many believe he was born on July 5. He described himself as white but with a dark complexion, 5’3” tall and 125 pounds. On the form he renounced his allegiance to Ferdinand I, King of Romania. Max became a U.S. citizen on April 17, 1919 (Certificate of Naturalization no.1149681). According to the 1920 Federal Census he lived with his parents, brother and brother’s family (wife Molly, children Stella, Jerome, Sidney) at 403 Girard Avenue North. Interestingly, they lived next door (#407) to a family of immigrant Grossmans who had come from Russia in 1891, and were apparently unrelated to our family; these were Joe, Jennie, Annie, Ida and Stella. All the Lorberbaums spoke Yiddish as their first language. Max was employed by Minneapolis Steel Company, which later became Minneapolis Moline.

Max and Celia Lorberbaum’s wedding photo, circa 1920 Sometime around 1920 he married a Romanian Jew named Celia Ursula Kohen, daughter of Alex Kohen and Rose Segal.

Rose Segal Kohen, circa 1944

Max and Ceil with children Alene, Avis and Howard, circa 1932 They started dating when Bud was about 15 years old and were married on January 1, 1942, in the darkest moment of World War II. My grandfather remembers fondly the Lorberbaum household when he was a teenager: “I was there more than I was in my own house. And they were wonderful people. [Max Lorberbaum] was just a great person... He had had a very hard life. And he adored his family… He worked for a big company and he was very successful. Minneapolis Moline was the company he worked for, and it was among the biggest companies in the state of Minnesota at that time, and he was a vice-president…

Minneapolis Moline, Lake Street and Minnehaha, 1895

Minneapolis Moline, Hopkins plant, circa 1925

Minneapolis Moline tractor, 1955 He worked his way through school and went to law school, William Mitchel, became a lawyer—never practiced… He was a very mild-mannered person. I never once heard him say a negative thing about anybody in his whole life… and he adored his family. His wife was a very strong-willed person, a very handsome woman...a great gourmet cook… She died a few years afterward, and she was a very sick person the last years of her life, arthritis and so on. She was the manager of her children, Ceil.” John Marcus recalls that the Lorberbaums lived only a block away from his family: “I knew of Max because he was sort of unusual... He was quite a smart cookie. He worked for Minneapolis Moline and he rose up in the ranks, which was very unusual for a Jewish person, so he was very well respected. Everybody knew who he was.” My own father, Richard (Dick) Grossman, had the following to say about his grandparents: “Max and Ceil were angels, human jewels: their love and kindness brightened the lives of everyone they knew. Max was very wise and very sweet. Ceil was tough, super-bright, with a thousand opinions on every issue. She was larger than life and lived for her family.” Returning to B’nai Abraham, in 1920 the congregation moved to 13th Avenue South. The synagogue had its own Talmud Torah until 1927, with 350 children attending, but in that year it merged with Minneapolis Talmud Torah. By 1952, largely because of the post-war flight to the western suburbs, there were only fifteen families left supporting the old synagogue. As a result, in 1956 the congregation moved to a building at 3115 Ottawa which had been converted for the purpose. In the same year there were only 27 families attending, but by fall, 1959 there were nearly 400.

Tifereth B’nai Jacob Synagogue, second location on 810 Elmwood Avenue, 1948 Tifereth B’nai Jacob congregation was founded in 1915 on North Emerson Avenue between 8th and 11th Avenue North. Like Mikro Kodesh it had no rabbi in the early days. In 1925 the congregation moved into a new edifice on North Elwood Avenue and 8th Avenue North and within a year there were about 100 families attending. Awend explains that Israel Friedman was the first “spiritual leader” of the synagogue, but was replaced in 1947 by Rabbi Kalman Friedman, an Italian. The latter left in 1950 after he failed to convert the congregation to Conservatism. From 1950 to1955 Rabbi Menachem Goodman from Chicago was rabbi, but by the following year the congregation had dwindled to a few dozen families. After a failed attempt to merge with Kenesseth Israel, which was also struggling along, the main building of Tifereth Jacob was sold and the congregation was moved to the Peretz Community Center on Plymouth Avenue North. In 1959 a new synagogue was built on a lot purchased on Xerxes Avenue North and membership increased to 60 families. Four years later the congregation voted to become Conservative and joined United Synagogues of America. By 1967 nearly 350 families attended. Mikro Kodesh, which had failed to merge with B’nai Abraham in 1966, successfully merged with Tifereth B’nai Jacob in 1968. The newly formed congregation, appropriately called Mikro Tifereth, was situated west of the city in Golden Valley. Thus, Mikro Kodesh, which had been both the first and last synagogue in North Minneapolis, was quietly retired after 76 years of service. My great-grandfather Max Grossman, Moishe’s son, was deeply involved in the life and administration of Mikro Kodesh and served the congregation in various capacities for decades. In 1972, after only four years of existence, Mikro Tifereth merged with B’nai Abraham, giving birth to B’nai Emet Congregation, currently located on Highway 7 in Saint Louis Park. Three synagogues which were not part of this series of mergers but which nonetheless were important in the community of North Minneapolis were Beth El, once located on North Penn and 14th Avenue North, Sharei Zedek, at 726 Bryant Avenue North, and Adath Jeshurun, built in South Minneapolis in the period after World War I. By the 1960’s most of the orthodox shuls had embraced the new Conservative movement and its precepts, which call for a significantly lower level of observance and study.

Beth El Synagogue, 1349 Penn Avenue North, 1926

Sharei Zedek Synagogue, 726 Bryant Avenue North, 1936 To sum up, when Jews first arrived in Minneapolis they settled in the area around Washington Avenue North. Between the late 1890’s and 1920’s, with the sudden expansion of the Jewish population, there was a decisive demographic shift to the neighborhood surrounding the intersection of Lyndale and 6th Avenue North. However, as Guita Gordon points out, “By the early 1930’s, Plymouth Avenue had taken the place of 6th Avenue North as the business street of the Jewish community.” The children of the first wave of Jewish immigrants started to marry and purchase their first homes to the north and west of downtown, where Jewish businesses came to number in the hundreds. By the outbreak of World War II, North Minneapolis had become home to many thousands of Jews. It was a veritable culture within a culture, combining the American way of life with traditional Jewish values. Gordon writes, “The bakeries, grocery stores and delicatessens were [on Plymouth Avenue] and it became a center, not only for shopping but for socialization. One could easily tell that it was the time approaching Shabbat because the women of the community were shopping for meat, fish and shallot in order to plan and execute their Shabbat dinner.”

Plymouth Avenue North from Washington Avenue, looking west, 1955

Plymouth Avenue North, looking west towards Morgan Avenue North, circa 1940

Plymouth Avenue North, looking west across Dupont Avenue North, photo 1940 John Marcus, born in 1917, recalls that when he was a kid the 6th Avenue North area had already been pretty well deserted by the Jews. Plymouth Avenue was the main street he remembers when he was growing up. “It was a very close neighborhood. The Jewish people who lived there all knew each other.” There were no tenements and very few apartment houses. The majority of people lived in single-family homes. Nobody seemed much wealthier than anyone else and their were no social strata amongst the Jewish community. Everybody intermingled. When John lived on North 6th Street there were still some horse-and-buggy wagons parked behind the houses, and some were still driven. But by the time he and his family moved to North Thomas in the 1920’s, with very few exceptions one saw only automobiles. Nevertheless, “peddlers would still come through the alleys picking rags and what not, and there was a lot of harassment of those poor people.” How quickly people forget their humble origins! According to John, Minneapolis was an anti-Semitic town. “It was written up by a sociologist named Carry McWilliams. The Silvershirts were in Minneapolis, a far-right anti-Semitic organization… People who moved into gentile neighborhoods were harassed. The Auto Club wouldn’t take Jews. Bud [Grossman] was one of the first Jews in the Minneapolis Club. George Stillman [Moishe Grossman’s son-in-law] was the first Jew in the Lion’s Club. Saint Paul was entirely different, and was more open than Minneapolis.” With regard to the Silver Shirts, I discovered an article from the Minneapolis Journal by Arnold Sevareid. It is dated September, 1936 and entitled “New Silvershirt Clan With Incredible Credo Secretly Organized Here:Weird Order, Beset by Unbelievable Fears and Hatreds, Claims Six Thousand Members in Minnesota. The article begins: “You probably won't believe this story. It concerns an organization now active in Minneapolis — known as the Silvershirts. It concerns secret meetings, whispers of dark plots against the nation and the Silvershirts’ incredible credo. Members of this organization talk about ideas and goals so fantastic that anyone who has heard them in meeting as I have goes away wondering if he still lives in America in 1936. Then he wonders if Sinclair Lewis could have been wrong, after all, when he wrote ‘It Can't Happen Here.’” Predicting a takeover, one Silvershirt told Sevareid: “In Minneapolis they are going to start through Kenwood and sweep eastward around the lakes and thence across the city.” On the American Jewish Historical Society website an ongoing series, Chapters in American Jewish History, has been published since 1996. Chapter 70, entitled “But They Were Good to Their People”, documents Jewish gangsterism between the wars: In Minneapolis, William Dudley Pelley organized a Silver Shirt Legion to “rescue” America from an imaginary Jewish-Communist conspiracy. In Pelley’s own words, just as “Mussolini and his Black Shirts saved Italy and as Hitler and his Brown Shirts saved Germany,” he would save America from Jewish communists. Minneapolis gambling czar David Berman [Could he be a relative?] confronted Pelley’s Silver Shirts on behalf of the Minneapolis Jewish community. Berman learned that

Silver Shirts were mounting a rally at a nearby Elks’ Lodge. When the Nazi

leader called for all the “Jew bastards” in the city to be expelled, or

worse, Berman and his associates burst in to the room and started cracking

heads. After ten minutes, they had

emptied the hall. His suit covered

in blood, Berman took the microphone and announced, “This is a warning.

Anybody who says anything against Jews gets the same treatment.

Only next time it will be worse.” After Berman broke up two more

rallies, there were no more public Silver Shirt meetings in Minneapolis. Turning back to North Minneapolis, Marion Shapiro, a granddaughter of Moishe Grossman, recalled that “in the old days family was entertainment. You didn’t go to the movies. You didn’t have cars. You used to go to peoples’ homes.” Marion, born in 1916, claims that she remembers the neighborhood when she was five years old: “North Minneapolis was mostly Jewish in a certain given area. It was like a small town… It had its delicatessen. It had its butcher shop, movies…” She and John Marcus told me that very few people used to go out to eat in restaurants. Families gathered together in their homes at mealtime. Aside from being prohibitively expensive to eat out it was difficult to find kosher food in restaurants. Harold Grossman, Lou Grossman’s son (another of Moishe’s grandchildren), added, “One thing I think is very important to know… In that era, all visiting was done with relatives. There were no outsiders ever there, nobody from outside the family.” Norman, Harold’s older brother agrees: “There was so much family anyway… we never got out of that circle.” Norman, born in 1914, remembers what it was like to wander around Minneapolis when he was a youngster: “When we [Harold and I] were younger we used to go downtown on the streetcar, and I would quite often get lost because the crowds were so great... when I was like five or six years old. My mother would let go of my hand and I’d turn around. There’d be a million people swarming around, and I’d say, ‘Hey Mom, where are ya?’ Now that was around the Dayton Company because that was the center of Minneapolis’s downtown… and Donaldson’s was kitty-corner across the street.” |